A Review of Philipp Felsch’s How Nietzsche Came in from the Cold: A Tale of Redemption (2024)

Evil at one time or another seems good to him whose mind a god leads to ruin, but only for the briefest moment such a man fares free of destruction.

—Sophocles[1]

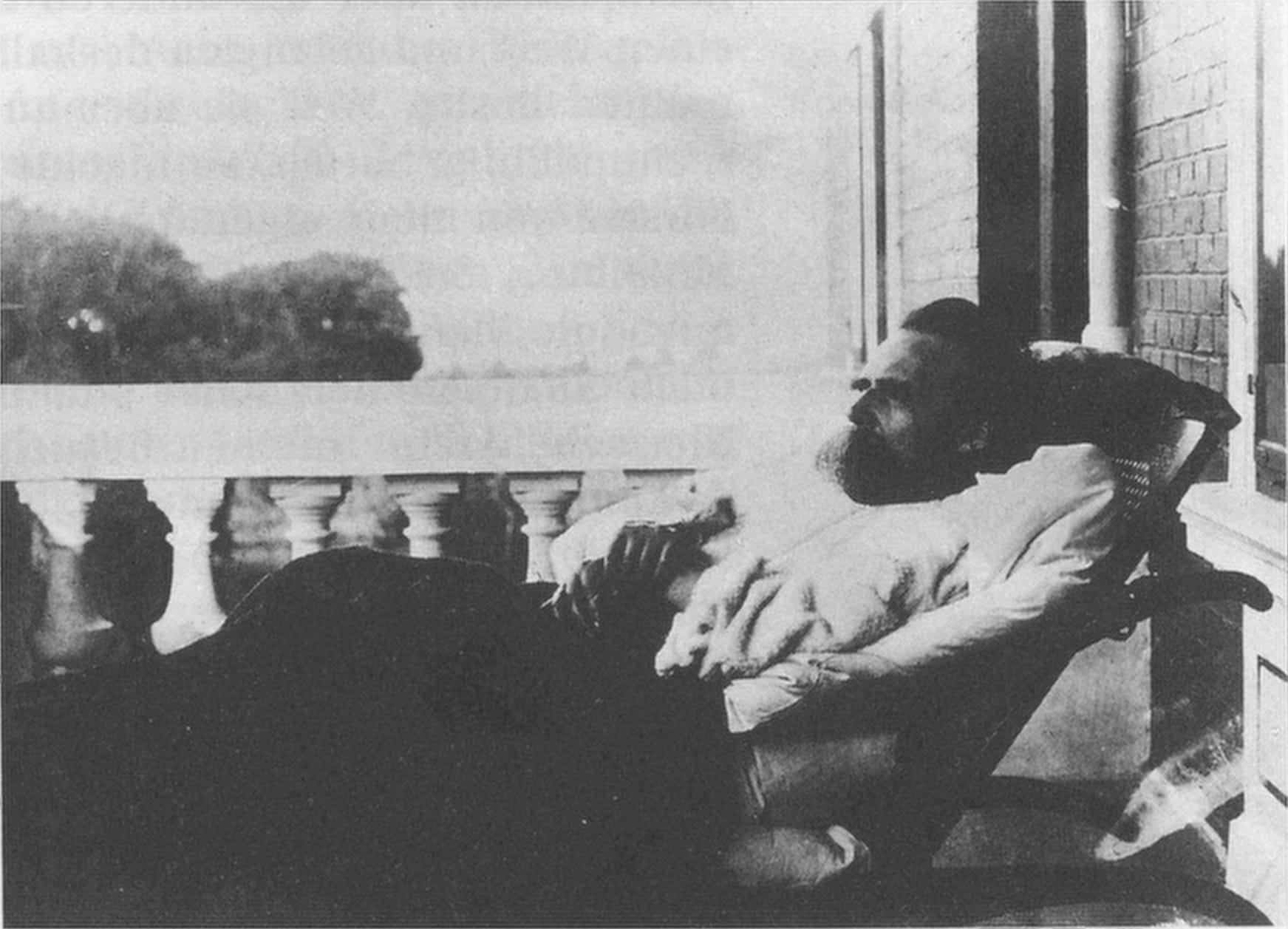

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was an unsystematic thinker who wished to be "unfashionable." Yet, from 1930s fascists to 1970s theorists, his aphoristic style has lent itself to widespread but diverse appropriation. Today, his image—resembling a gruff walrus—has become synonymous less with a specific programme than a subversive energy, converting myriad teenagers, autodidacts, and academic manqués into standard-bearers.

Nietzsche’s costume range is not particularly unusual (even when he’s posing as a horse), nor for that matter are his divided acolytes. Georg Hegel and Carl Schmitt also had legacies split by political tribes. Nonetheless, his esotericism—celebrated by Georges Bataille’s Acéphale Society among others—became a great object of fascination, comparable to the likes of Pico de Mirandola in the Quattrocento or the theurgical maestros of Neoplatonism.

Nietzsche’s flame, however, faded in the decade that followed WWII, mainly due to his acquittal as the godfather of Nazism—shame migrated instead to the editorial efforts of his fascist sister Elizabeth—as well as his portrayal by Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Walter Kaufmann as a remote existentialist precursor. Hence Jurgen Habermas’ ability to write, half hopefully, that “nothing contagious anymore” emanated from Nietzsche as late as 1968.[2]

The sputtering lamp, however, was never quite snuffed out. Some portrayed Nietzsche as an off-ramp from modernism to classical equanimity. Others saluted his Dionysian elements and framed the German as an exit from the neo-Hegelian cult of history, whose ubiquity among western scholars formed proof of their living in the twilight years of a dying European culture. Few took heed, however, until Michel Foucault argued that Nietzsche—alongside Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx—had destroyed the notion of an authentic text, replacing it with an abyss of interpretations and relativist assertions that reduced truth to a fiction, the unity of self to an illusion, reason into an avatar of power, and history into a record of flux with little inherent meaning.

Here, the historian Philipp Felsch steps in with his book, How Nietzsche Came in from the Cold: A Tale of Redemption (2024),[3] to recount the efforts of two obscure Italians, Giorgio Colli (1917-1979) and Mazzino Montinari (1928-1986), as they mounted a rearguard action both to defend the traditional practices of textual exegesis as well as the ideal of recovering a “real” Nietzsche from his Nachlass [notebook] material.

In many ways, the book replays the drama of Nietzsche’s first publication The Birth of Tragedy (1872), which was a visceral alternative to the prior understanding of Greek culture inspired by Johann Winckelmann’s History of Ancient Art (1764). Setting Dionysian principles of poetic inspiration over and against Apollonian ones like the theoretical optimism of Socrates, Nietzsche portrayed the latter as revolutionary who taught that people could rise above merely living out their own personal tragedies, and instead believe in the possibility of philosophical truth and separating such knowledge from fallacy. In Felsch’s volume, the two Italian protagonists are shown to push an epistemological outlook that closely mirrors the interrogative manner of the Athenian gadfly. This is a bold undertaking considering that Nietzsche tended to assume an anti-Socratic stance throughout his work.

Convinced that the grand claims of metaphysics had been upturned by two world wars, Colli annexed Nietzsche to his dream of sacralizing western culture: to return thinkers to the groves of Hellas to start afresh, break ranks from the modern hubris that all laws could be discerned and controlled, and present Nietzsche as an ad fontes figure who wished to return to the hoary practical question of how to live well. Meanwhile, the Communist Montinari viewed Nietzsche as a radical figure of the enlightenment, a proponent of insights won through stringent methodology––a sort of Descartes on steroids.

The project yoking this pair of wild horses set out to liberate Nietzsche from bad faith interpretation by translating 10,000 barely legible pages housed behind the Iron Curtain. As these were located in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), where the philosopher had been officially designated an enemy of the state, theirs was a herculean task. The key message from the Italians was that Nietzsche should be treated more like Aristotle, that is with disciplined commentators carefully inching his precepts forward, rather than as ragdoll pushed hither and thither, fulfilling the hero or scapegoat roles as academic careers required.

Running through the archival micro-drama of Colli and Montinari’s translations was the question of Nietzsche’s intellectual reception, and needling each fiber were countless acts of philology, a discipline that Nietzsche once taught yet later dismissed as “science for cranks” and “repetitive drudgery.”[4] Just as the pair turned Nietzsche into a modern-day Socrates, a man whose thought Nietzsche viciously critiqued, their work made use of a discipline that Nietzsche came to despise, perhaps almost to the point of pedantry.

Several contemporaries agreed, openly worrying that Colli and Montinari risked arresting Nietzsche’s formidable intelligence through the petty over-interpretation of minutiae. Jacques Derrida, for example, noted that the pair had busied themselves erecting a “monument to hermeneutic somnambulism.”[5]

It is equally clear, however, that Nietzsche would have also deplored the French position of relativized textual meaning. He did not argue for the negation of Socratic culture, of moral questioning towards the good, but instead diagnosed “the self-overcoming” of the Platonic-Christian regime of truth as inevitable—for, he writes, “all great things perish through themselves.”[6] In claiming he was not just “decadent” but also a new “beginning” in his last work, Ecce Homo (written 1888, published 1908),[7] Nietzsche critiqued the French School before it had been born. Damningly, he wrote in The Case of Wagner (1888) that its worldview displayed a “literary decadence” in which

The word becomes sovereign and leaps from the sentence, the sentence spreads out and obscures the meaning of the page, the page gains life at the expense of the whole, and the whole can no longer be called such. This is symbolic for every style of decadence.[8]

More to the point, the inquiries of the Italians reaped rewards which suggested, in their own modest manner, that a paragraph of scholarly elbow grease was worth several pages of theoretical bumf. They discovered, for example, that Nietzsche had almost certainly not planned The Will to Power (written in the late 1870s and 1880s, published 1901) as a finished text when he lost his mind, as he had already published the notes he considered worthy only in his final books: Twilight of the Idols (written 1888, published 1889) and The Antichrist (written 1888, published 1895). Moreover, the philosopher had also often boldly lifted material from the likes of Wagner, Tolstoy, and Renan, casting doubt on much of his originality. The overall result, however, was not so much a different philosopher than a smaller pedestal; a Nietzsche cut down to size as a pastor’s son; a brilliant straggler of the Romantic epoch who waged a neurotic battle against the forces of his own past, from Christianity to Wagner and Schopenhauer.

Feslch’s book has a few shortcomings. Most obviously, the lives of the Colli and Montinari only haphazardly reward the weight of scrutiny thrust upon them. Furthermore, the intelligentsia’s habit of mistaking snark for discernment is rarely filtered, resulting in a text that is fitfully more annalistic than sharp. Painting a cultural backdrop to parlor games can be a worthy cause but—like an ornate retable over an altar— distracts from the real action. Finally, Felsch is elusive as an authority. While heavy editorializing is best reserved for polemics, its total absence in How Nietzsche Came in from the Cold often leaves the reader without a steer on questions that a stronger voice might aid.

Such criticisms should not detract from Felsch’s achievements, however. Executing a romp through intellectual history that demonstrates impressive knowledge of typical lacunae like Italy’s postwar politics, while avoiding patronizing academics or fatiguing a general audience, is no mean feat. Moreover, the author is a wry, sympathetic observer who has knitted diverse intellectual genealogies seamlessly together to produce something closer to reportage than just another Bertrand Russell-adjacent history of philosophy. The result—as with his previous book, Summer of Theory: History of Rebellion (2021)[9]—is a rigorous yet spry account on the powderiest pillar of the humanities, philology.

The problem with such a tour de force of an intellectual-reception history is that Nietzsche, endlessly glossed, recedes into the background of his own story. This is frustrating for those who wish for critique rather than mere context-setting. The German’s famed acerbity leaves most readers guessing the scale of his detonation but, if properly appraised, Nietzsche’s attacks are strongest when dismantling human hypocrisy, vanity, and bluster—a modern update on the Jewish Kohelet, the Christian Ecclesiastes—and weakest when claiming that nature or reality is patterned on the same abyss. Nietzsche’s truth bombs—far from being the nuclear warheads of his fans—are more like grenades, destroying a lower order logic of civilizational shibboleths while professing to expose the deeper nature of truth and power.

Superficially, Nietzsche and Christians can be seen as allies, scourging the world of a hypocrisy that flourishes among the jostling tenets of rationalism, tradition, and comfort. Nietzsche, however, tends to discount society as hopelessly regressive, only to promote a form of hyperindividualism that creates a better class of victor and victim. Conversely, in passages like John 12, Christ favors devotion to the truth over performative concern for the poor because society can be redeemed––it is the cure as well as the problem.[10] In brief, the philosopher is offended at the status quo in the manner a serious crook like Judas might scoff at petty theft—as St. Augustine noted, why lead a gang of robbers when states (if without justice) are run on the same principles[11]—Christians take umbrage because it excoriates the world’s higher nature.

This confrontation is usually formulated so that Christians appear as dim, pious creatures who prefer revelation over Nietzsche’s erudition out of a misplaced sense of fideistic loyalty. Typically lacking in such accounts is the fact that neither side works off a large body of empirical evidence, as both Christ and Nietzsche communicated in counterintuitive soundbites rather than exhaustive programmes. The PR coup of the Nietzschean camp lies in the German’s dismissal of the faith as a slave morality, but the accuracy of the accusation depends on the highly contestable view that the agon of the olympians—rather than, say, the agony of the cross—has a monopoly on ‘life-affirming’ values.

Confession is the best symbol of this division. An act of debasement to Nietzscheans is, in the eyes of Christians, a taste of divine freedom, for freedom cannot exist outside of the truth; nobody can be free in cages of lies. Confession grounds people in truth by attacking falsity’s foundation: self-deception. To Christians, real slave morality is not merely the default of the fallen masses who adjust their worldviews when coerced or manipulated by the powerful—a dynamic that also repelled Nietzsche—but also the default for an elite who are not just corrupted by power, but are unable to conceive life outside its limitations, resulting in highly stunted life-forms.

Equally, Nietzsche sought to supersede thought itself––a project to which Jacques Lacan appeared aligned when he parodied Rene Descartes with the observation that “I think where I am not and am not where I think”[12]––whereas the Church understood faith as an epistemic state; the two spheres standing enmeshed rather than in competition. Conversely, Nietzsche prefigured literary theorists in claiming thought as little more than the sum of psychological forces, material interests, and networks of power. But his attempt to identify a meta-discourse resulted in madness and not revelation, thus recalling Sophocle’s warning that those “whom the gods would destroy, they first make mad.”[13]

Similarly, time meant to Nietzsche little more than the prospect of eternal recurrence,[14] a dismal admission which acknowledged that power lacked the means to change the world. Yet to the Christian, metanoia (another symbol of slave morality to Nietzscheans) ensures hope can spring eternal. This hope is central to any form of meaningful time: time being not just a chance for personal salvation—and thus time as an expression of God’s hope in us—but an opportunity to improve the world by installing God’s Kingdom. That allows us to live in divine freedom and be true to oneself and to others. People are not doomed by the world, but, enabled by the imago Dei, bear a responsibility as co-creators to spur its redemption, a task rewarded with a peace which “passeth all understanding.”[15] Time is simply another word for grace which, undeserved, instills gratitude into creation.

Such a gratitude refuses to privilege even the faithful over the gentiles. Notice how (in one of my favorite biblical verses) the author of Hebrews records the odd way God acknowledges the faithful in ancient Israel who were “stoned, sawn in two, killed with the sword, mocked in skins of sheep and goat, destitute, afflicted, ill-treated, wandering over deserts and in the dens and caves of the earth, though well-attested by their faith.” For all their examples of heroic faith, these saints “did not receive what was promised because God has foreseen something better for us, seeing that” in being “apart from us they would not be made perfect.”[16] This line indicates that we, as children of God, are inseparable from each other, and that God’s Kingdom is a non-partible and inalienable inheritance.

While in his final years of bed-ridden madness, Nietzsche suffered so profoundly that he was moved to pity a beaten horse and thereby lost his mind. And yet it is not clear why he bothered. On his account, his being mocked, destitute, afflicted, ill-treated, and left wandering, accomplished nothing except typifying the sort of pathetic example he despised. Only by the measure of what he critiqued, and sought to surpass––the slave morality of Christianity––could his ordeal (as a beast of burden in his own right) at all be judged meaningful. Perhaps the lesson of his breakdown with the turinese mare is that in his obsession with the will to power, amor fati, and isolationist forms of self-perfection, Nietzsche revealed his inability to confront suffering meaningfully, yet ended his sane life practicing compassion––or the “virtue of prostitutes,” as he called it.[17]

Finally, Nietzsche glamorized the removal of past restraints on the will-ego which, when governed by intellectual brilliance rather than spiritual maturity, resembled a mercurial teenager rather than an exemplar. In contrast, Christ understood that the world had fallen so far that he presumed an ignorance (of mankind’s divine trajectory) would afflict even his closest followers. In Matthew 20, when Christ predicted his fate to the disciples, James and John (spurred by their mother) took him aside to request special favors in heaven, causing outrage among their peers. A scene which demonstrated that the Roman patron-client relationship trumped divine wisdom––as the sophia of the Orthodox liturgy points out, humility is the true nature of knowledge; to accrue facts without this disposition is to possess them in much the same way a magpie does pilfered trifles in his nest––in even Christ’s closest associates.

Christ’s response is worth quoting fully, as he not only reminded them that blessings attend sacrifice, not favors or manipulation—‘Are you able to drink the cup I drink?’—but that the fallen gentile mindset is to be set aside:

Those who rule the Gentiles lord it over them, their men exercise authority over them. But it shall not be so among you: whomsoever will be great will be their servant, whosoever will be first among you must be the slave of all. For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, giving his life as a ransom for the many.[18]

Today, despite a post-Christian society that oscillates between puritanism and hedonism, it remains unclear that greatness is associated more with Nietzsche’s outlook rather than Christ’s vision. If the latter’s spirit has been abandoned, at least the letter of biblical communal ethic has been preserved in the fraying norms of social democracy, hence clarion calls by X’s Nietzscheans for its dismantling.

Audiences tend to take the latter’s colorful programmes seriously, if only because states are often parodically bloated, dysfunctional, and corrupt in ways that chime with Nietzschean criticism. Moreover, they share a sense that Nietzsche has in some way been betrayed––if only because of the imposture of intellectuals who make constant references to Nietzsche, Bataille, and Sade, while adhering to a democratic morality which contradicts the radical nature of their analysis.

Perhaps gratitude is owed to their hypocrisy when the greatest Nietzscheans of the age, to take one extreme example like Mao Zedong, pushed events such as the Great Famine (1959-62) which starved 33 million, onto history’s pages. Yet Mao, famously subject to neither ‘law nor god,’[19] suffered a similarly dismal death to his precursor. Much like Homer’s cyclops, the Chinese leader finally became the 20th-century’s own Polyphemos in his last years of decrepitude,[20] and serves as a reminder that Nietzsche was wrong: to try to assuage or overcome life’s pettiness or limitations by revving it into overdrive––or taking an accelerationist turn––is really to indulge an iteration of the death drive, thanatos . . . and reap the whirlwind.

In contrast, personal lives of holiness tend to demonstrate that, at its most profound, truth mirrors the Trinity’s perichoresis, embroiling love, forgiveness, and sacrifice. Love means that all inheres in all; forgiveness follows from a grace that is not only received, but invites participation and dissemination; and sacrifice provides love with its greatest stamp as its chief dynamic is distilled into a single action;[21] a principle around which the universe is mysteriously structured. Put bluntly, our lives tend to provide empirical evidence that bears these truths out, even if power, apathy, and cynicism take their pound of flesh too.

Conversely, when the Nietzschean virtues of the overman—who overcomes and owes nothing to anyone, not even God—are practiced, this victory “over” life finds expression only in its subversion, even destruction, rather than any manner of fulfillment. It is merely the victory of ego over life. Moreover, this “triumph” is accompanied by disorders that resemble the interior trauma of civil war.

On this subject, both classical authors and the bible concur that such external conflicts flow from a deeper spiritual war: stasis almost destroyed Athens before Solon’s intervention, just as Christ warned the Pharisees that divided houses fall.[22] As attested by this universal sense of dissolution, when mankind tries to confront his condition on its own he either ends up mad or bad until broken.

Even as some postmodern theorists understood, a man cannot belong to himself unless he is “delivered over to the other” as other.[23] Likewise, only by participating in Christ’s fearsome love, the love that watches nails driven into its own flesh; that considers humiliation par for the course; that intercedes with the Father in every waking breath to forgive its persecutors; are we permitted access to powers that would see Satan fall like lightning from heaven.[24]

Sophocles, Antigone, lines 620-625 (Chorus), trans. Sir Richard Claverhouse Jebb (1891), online. [Slightly modified from original.] ↩︎

Jurgen Habermas, “Nachwort,” in Friedrich Nietzsche, Erkenntnistheoretische Schriften (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1968), 237. ↩︎

Philipp Felsch, How Nietzsche Came in from the Cold: A Tale of Redemption, trans. Daniel Bowes (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2024). (Cited as HNCC for the sake of brevity.) ↩︎

Quoted in Felsch, HNCC, ibid, 9. ↩︎

Quoted in Felsch, HNCC, ibid, 147. ↩︎

“All great things perish through themselves, through an act of self-cancellation: thus the law of life wills it, the law of the necessary “self-overcoming” in the essence of life…”

Frederich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals (3.27), trans. Maudemaire Clark and Alan Swensen (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Co., 1998), 117. ↩︎“This double origin, taken as it were from the highest and lowest rungs of the ladder of life, [is] at once a decadent and a beginning…”

Frederich Nietzsche, “Why I Am So Wise,” Ecce Homo, trans. Anthony Ludovici (1911), online. ↩︎Frederich Nietzsche, quoted in Walter Kaufmann, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974), 73. ↩︎

Philipp Felsch, The Summer of Theory: History of a Rebellion, 1960-1990 (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2021). ↩︎

“Six days before the Passover, Jesus therefore came to Bethany … Mary therefore took a pound of expensive ointment made from pure nard, and anointed the feet of Jesus and wiped his feet with her hair. The house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume. But Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (he who was about to betray him), said, “Why was this ointment not sold for three hundred denarii and given to the poor?” He said this, not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief, and having charge of the moneybag he used to help himself to what was put into it. Jesus said, ‘Leave her alone, so that she may keep it for the day of my burial. For the poor you always have with you, but you do not always have me.’”

John 12:1-8, ESV. ↩︎Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms? … Indeed, that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, What you mean by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, while you who do it with a great fleet are styled emperor.”

St. Augustine, City of God (4.4), trans. Marcus Dods (1887), online. ↩︎Jacques Lacan, quoted in Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983), anniversary edition (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 147. ↩︎

Sophocles, Antigone, ibid. This is the common english paraphrase of the latin idiom: Quos Deus vult perdere, prius dementat. ↩︎

Nietzsche's posthumously published notebooks contain an attempt at a logical proof of eternal return, which is based upon the premise that the universe is infinite in duration, but contains a finite quantity of energy, forcing it to a finite amount of combinations which must end up repeating. ↩︎

“...do not be anxious about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.”

Philipians 4:6-7, KJV. ↩︎Hebrews 11:36-40, ESV. ↩︎

“Compassion is the most agreeable feeling for those who have little pride and no prospect of great conquests; for them, easy prey––and that is what those who suffer are––is something enchanted. Compassion is praised as the virtue of prostitutes.”

Frederich Nietzsche, The Gay Science (1.13), trans. Josefine Nauckhoff (with Adrian Del Caro), ed. Bernard Williams (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 39. Contrast Nietzsche’s original worldview with that of St. Paul who, in order to avoid the onset of pride that inevitably accompanied grand narratives––which in his case was theoretically justifiable given his propagation of the Gospel––the saint commended the divine wisdom that installed ‘A thorn in [his] flesh, a messenger from Satan, to prevent pride/conceit’ (2 Corinthians 12:7). ↩︎Matthew, 20:20-28, ESV. ↩︎

Ross Terrill, Mao: A Biography (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999), 17. ↩︎

Mao barely had any teeth from 1970 onwards, smelled homeless because he refused to bathe, suffered from Parkinson’s disease as well as various venereal issues, and in his final years became virtually deaf and blind. ↩︎

“Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends.”

John 15:13, ESV. ↩︎“And if a house is divided against itself, that house will not be able to stand.”

Mark 3:25, ESV. ↩︎Once Jacques “Derrida mentioned [Emmanuel] Levinas in the opening session of his seminar, drawing attention to his work on the origin of ‘pity, compassion, forgiveness and closeness’, and to a tantalising remark about selfhood: ‘The word “I” answers for everything and everyone’ (‘Le mot “je” répondrait de tout et de tous’). What Levinas meant, according to Derrida, was that I cannot ‘belong to myself’ unless I am already ‘delivered over to the other’ – and hence that we are all members of one another, and constitutionally incapable of being wholly self-centred, self-sufficient or self-contained.”

Jonathan Rée, “No Foreigners,” London Review of Books, Vol. 16, No. 19, 10 October 2024, online. ↩︎“And he said to them, ‘I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.’”

Luke 10:18, ESV. ↩︎

Henry Hopwood-Phillips is a historian and founder of Daotong Strategy. His work on Byzantine history can be found at his website Byzantine Ambassador. He invites you to follow him on X.