Three years into Donald Trump’s first term and The American Mind’s writers have been thinking a lot about self-government lately. They are discouraged by what they see. In their eyes, much of the country is a shambles with basic institutions—schools, churches, and families—in tatters. All the while, the administrative state, that great conservative bugaboo, continues to gather the powers “rightfully reserved” for localities, the reservoirs of individual self-governing energies.

These writers lament that, for years, conservatives have known precisely the sources of social and political ailments, able even to recite their stages by heart. All good American conservatives, writer Lane Scott argues, can identify the three waves of progressivism. First, Woodrow Wilson planted the seed of anti-Americanism deep in the heart of the federal government. Then, Franklin Roosevelt grew that seed, spawning the dreaded administrative state we recoil in fear from today. Finally, Lyndon Johnson christened the modern welfare state. Each man drove the stake deeper in the heart of the American Constitution, then resurrected it as something unrecognizable.

Of course, since Johnson left office in 1969, the only real progressive president the country has seen since was reluctant to institute anything that even whiffed of nationalized medicine. Meanwhile, Republicans saw twelve years of uninterrupted rule, snapped by basically-Republican Bill Clinton, and then resumed by another two-term president. We are in agreement with Mind’s authors that not much has changed since the Reagan Revolution, but we are of the conviction that they lament precisely the wrong things.

We further agree with Scott’s primary thesis, that Conservatism, Inc. has failed the GOP and the country. Yet, rather than interrogating the causes of this disappointment or even plotting a way forward, Scott has internalized and adopted the faults she sets out to critique. The fundamental misstep of modern conservatism is simple: the elevation of individual interest above all else. Conservative thought—no, the broader and omnipartisan American Mindset—is devoted to a narrow sense of entitlement that seeks individual and group advantage. To the extent that this American Mindset cites religious meaning or family life or insulation from material deprivation as goods, they are only good derivatively, and their realization may not tread on the talismanic goal of small government.

We hope to reinvigorate the American mind, promoting a healthy and inclusive localism, robust civic life, and a serious application of American values—of which the foremost is liberty and justice for all. But we emphasize: this promise is universal. The revitalization of American social and political life must be for all Americans. It cannot be achieved by an existential critique of government, further promotion of atomization, or policies that only support those wealthy or fortunate enough to avoid them. Instead, we find it necessary for conservatives and the country-at-large to overcome a fetish for small government, to recognize the consequences of atomized localism, and to chart an inclusive path forward.

A Small Government Fetish

Lane Scott writes that the skeleton of the American welfare state—Social Security, Obamacare, Medicare, and Medicaid—claims much of the nation as dependents and that conservatives have no plan to wean them off. But why should they wean them off? What precisely would this accomplish? Scott argues that in doing so we can reclaim the moniker “self-governing,” as if communities would rush to reclaim these responsibilities once they are wrested from the federal government. Where to locate the evidence for this claim is beyond us. Scott claims that conservatives must “believe that the government closest to the citizen is most accountable, effective, and just regarding almost everything the citizen needs.” The language of belief both in her and in the progressive case are apt; both serve more as articles of faith than as governing philosophies. But the conservative belief arises from the same problem that plagues these essays throughout: an amoral fetishization of small government.

President Reagan was very much mistaken with his famous line: “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.” Government, with its telos as the common good, is a way to solve communal problems. That is not to say that every minor concern requires a bureaucratic response, but the government alone can achieve many common goals—of which protecting personal liberty is but one of many equal goods.

The fetishization of small government has entirely blinded the modern conservative movement to the purpose of government and to the goods it is supposed to help secure. This is true both of the Mind’s authors and of the politicians they deride for being craven and ineffective, satisfied with playing a role in a narrative at the cost of losing political battles. Yet if the Mind’s authors lament this strategy, they fall into the same trap: they refuse to govern. Instead, they exhort individuals to take up the task, ignoring that the rise of the administrative state, whatever its virtues and vices, is the precise result of the unwillingness of both people and their legislators to govern. This also misses exactly what American voters are voting for.

Yes, many Donald Trump voters saw the Obama administration as a case study of executive overreach, yet they did not elect to change parties in 2016 so that their new president would dismantle the federal government. This is to conflate the preferences of the American voter with the preferences of the Chamber of Commerce. The former are often tyrannophobic, often to a fault, yet New Deal-era social welfare programs are among the most popular in the country, and for good reason. They enable people to achieve things that are good, and that we think the government is best able to provide. If scaling back Social Security benefits at all costs seems to trump providing comfortable retirements to senior citizens, then the fetishization of small government has clouded our thinking about the purposes of the government.

It’s telling that many choose to frame discussion of social welfare programs as that of “entitlements,” thereby vilifying anyone who through fault, circumstance, or tragedy needs help from their community. Alas, they say! What of those who abuse government assistance, who would rather depend on welfare than work for a living? Beyond there existing little evidence that such a problem exists or is widespread, questions of how to tailor policy are wholly separate from the moral obligation to support one’s neighbors. Besides, a just society would rather be fooled into generosity than refuse assistance to all who are in need. While private charity is a very great good and ought to be encouraged, it doesn’t replace the government’s responsibility to promote the common good for all those under its care. While charity ought to be encouraged, the prevailing libertarian approach necessarily selects recipients based on the passions of the donor and close compatriots, not for those within the community’s margins. The American promise for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness should not and need not be reduced to a fancy phrase for vulgar Lockean property rights and possessive individualism.

One of Scott’s repeated concerns is shifting the “burden of caring” or other tasks to a lower level of government—from federal to state, from state to local government. This formulaic devolution is concerning but grows to be terrifying when acknowledging the central claim of the American Mindset: communities are broken. While it is certainly true that the federalization of education policy and implementation of programs such as Common Core have caused harms, to remove federal and state oversight on education is just as mistaken when so many communities are strained and impoverished. There is a difference between decrying ineffective or idiotic educational policies and attempting to dismantle the governing apparatuses that could mandate better ones.

If a family is disappointed with the form or quality of school district-led education, the American Mindset would seem to suggest that two choices exist: find a private (if lucky, charter) school or move to a new district. From an individual standpoint, this is understandable if we think of parents as trying to maximize their children’s educational returns for the lowest price. Yet, it doesn’t even occur to those with an irrational fear of government that reform coming from federal and state Departments of Education may solve their problems. They are so reflexively opposed to public education—a public good, and not only in the economic sense—that they blind themselves to the powerful tools right in front of their eyes.

This makes their stance toward local government all the more confusing. If the regime is corrupted, it is not because governing isn’t done locally. There is nothing sacred about local government that will undo a pervasive unwillingness to self-govern, and the latter is antecedent to the former. If the regime is corrupted, then it is at all levels.

Even so, our question is whether devolving governing power to localities would enable people to live better, more meaningful lives? Can it solve an epidemic of suicides and despair that are, above all, existential crises? It is not at all apparent that localism is the means of undoing sclerosis and accomplishing this. It is not clear that conservatives have the ability to effect change in the majority of cities across the country.

Scott claims that “The war for self-government is being fought by an army of anonymous citizens who are slowly building back up the essential secondary institutions that centralization has destroyed.” But we are aware of no such army. To the contrary, the most effective attempt at local political engagement in recent memory has been the nationwide effort to get individual cities to defund or reform their police departments. The broader conservative movement sports no successes similar to the left’s local activism in recent decades. Despite Scott’s insistence that liberals only know how to legislate from the top-down, the left has been far more effective in grassroots organizing for the last few decades. While the timing and circumstances surrounding the defunding efforts may be unique, the trend forces one to consider that conservatives have been less concerned with self government in their communities than with personal autonomy outside of communities. As cities across the country are adopting policies that Scott and other conservative writers disavow, the only solution that they seem to offer is retreating and forming self-selecting, exclusive “communities.” While not all go so far in their withdrawal as the so-called Benedict Option, the construction of any sort of withdrawn, parallel institution is a difference in scale, not kind.

The Consequences of Atomized Localism

What writers like Scott advocate for is not localism in a sense that seeks to improve their community, but an atomized localism that seeks to redraw community borderlines around those with whom they agree or feel social bonds and to relocate control of community institutions within a narrow, selective group.

In part, this follows from mistaking communities for markets. This sad folly considers local institutions as fungible: if one doesn’t like their public schools, they should sacrifice to enroll in private schools; if one can’t find adequate health care, they should find a job with better coverage; and, if one can’t find solutions to neighborhood problems, they should move to another community. To “vote with your feet” is a luxury that the vast majority of the country cannot afford. Further straining this perspective, no one cannot just select and join a community at will, they are formed through years, and subsequently generations, of interaction and engagement with local institutions.

However, writers at the American Mind are increasingly supportive of sidestepping local institutions. A recent education symposium repeatedly advocated for charter schools and other alternatives to public education because, as Zachary Rogers writes, “the nuclear family provides the most effective and decentralized form of child-rearing proper for a republic... because it reduces the scope of government while providing the best environment to mold virtuous, independent, and contributing citizens who can sustain and enrich their society.” Rogers proposes that funds for public schools are further drawn down as parents choose to keep their tax money for homeschooling or use it to pay for private and charter schools. This unique mixture of small government, free market, and alternative schooling fetishism provides little evidence for how opting out of and reducing funds for public school districts would better serve individual education or the public good education provides.

We don’t want to see a wholesale dismantling of “school choice” policies, which largely serves as a dirty euphemism for parallel systems of education that sacrifice all public schools for the sake of exclusive semi-private education. Still, it is amazing that one could look at charter schools as anything but a symptom of hollow communities.

The point of improving a struggling education system deserves greater attention now and in future writing. However, it is certain that this American Mindset does not properly address it. Further, the causes of our educational crisis are most certainly not the destruction by centralization which Scott blames. A narrow, withdrawn localism has led exactly to a free market approach of community wherein families of means choose to live in proximity to one another for the sake of well-funded and higher-quality schools. As wealthy families continue to move for the sake of education, their former schools continue to lose funding, becoming overwhelmed and less capable. With time, this effect intensifies. By pulling resources, teachers, and students out of inclusive public schools to exclusive private and charter schools, the “choice” movement is choosing to condemn those in public schools to an inferior education. In the years to come, this will result in an emaciated society. It is hard to blame individuals for doing this, but this is precisely a role of government: solving complex collective action problems.

Beyond education, this deteriorating effect will be seen in communities across the country through distorted localism. While Scott says that “Part of being a complete person, after all, involves self-rule, legislating, and building one’s own community with one’s neighbors,” but the effect of her advocacy is homogeneity and deterioration. When one seeks to choose their neighbors forms a self-selecting community of homogenous values and, more realistically, finances, which will result in other dimensions of homogeneity. It is little surprise that such efforts, when entangled with racist public policy, have historically led to de facto segregation.

Packing up and leaving to found new communities does not just evince a blindspot on race and class, but it demonstrates an unwillingness to actually commit to community improvement. Those cities which have experienced mass outward migration—whether motivated “white flight,” politics, or otherwise—are left crumbling. Further, self-segregation as a practice in any domain will lead to increasingly tense divides throughout the country and weaken any ability for dialogue or collaboration between communities. Indeed, it’s not a challenge to love one’s neighbors when they’re specifically chosen for homogeneous agreeability.

Rather than retreating and forming their own enclaves, American conservatives should seek to assimilate within their own dynamic communities. The previous failure to do so has produced deleterious effects for American civic life. Conservatives’ lack of credibility in or understanding of the communities from which they have withdrawn has made them incapable of convincingly speaking to eternal and essential goods within our ever-changing society. Conservatives will never be presented the opportunity to turn back the clock, so hiding and withdrawing from broader society is futile.

A New American Mindset

It is a difficult task to revitalize conservatism and, in turn, American political life. Scott should be applauded for her desire to support communities and to work toward building a better society. As an engaged citizen and caring parent, she very well may be a model. Yet, she hasn’t escaped the type of “Grand Narrative” that she disavows and hasn’t recognized that government itself is not the enemy. No matter how many times the Chamber of Commerce, think tanks, or politicians insist, communal life is not a market that allows someone to pick and choose where they want to participate and where they want to be exempt from public institutions.

Admittedly, the work of revitalizing American political life or developing a “new American mindset” is a challenging one. False starts, including those at The American Mind, are useful for our society to help gauge what needs to be done and what options are available. Certainly, a renewed sense of localism—properly understood—will be a component of positive reform in the future. It is critical that we rebuild our communities to be both value-driven and inclusive. We will continue to work toward developing a new theory of culture and society that contains these elements and more. At the moment, we’re working on this effort by way of an upcoming symposium, discussing the possibilities for a just political economy.

The effort to improve our communities is urgent and necessary, Scott is right in saying that we must begin now: “Start building somewhere, commit to a certain place, and begin to live a full life now.” Indeed, that “What is needed at the national level is cultivation; a preparing and defending of the ground such that local platoons of citizens can sow and reap the harvest.” Il faut aussi cultiver notre jardin communautaire.

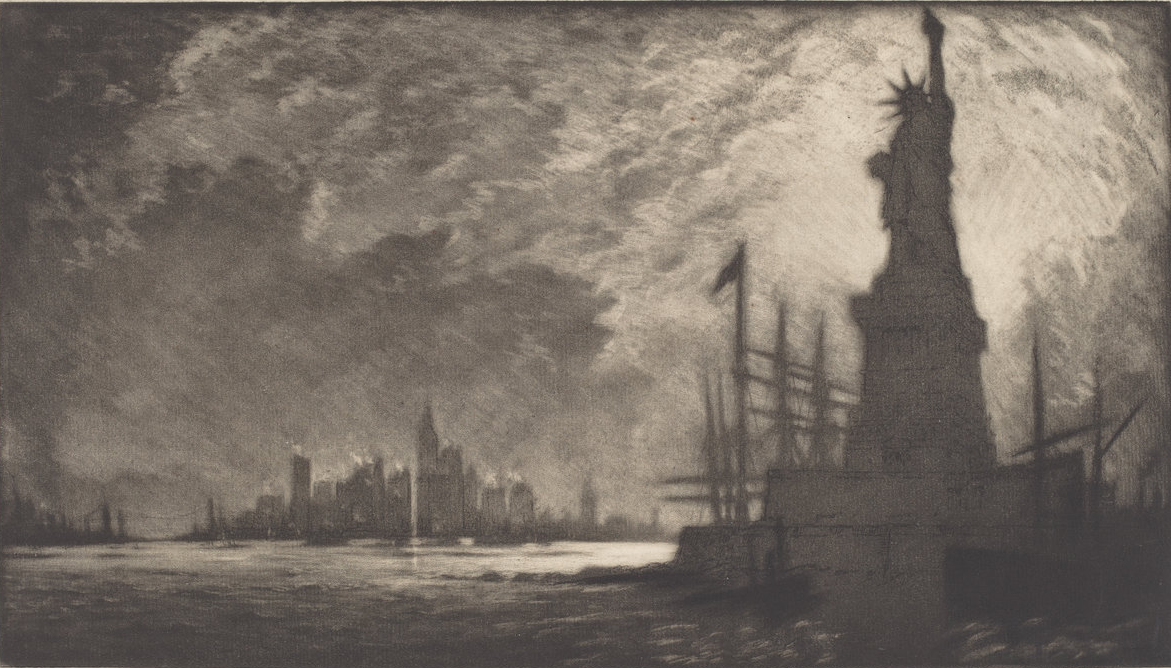

Featured Image: Hail America (1909) by Joseph Pennell via National Gallery of Art.

Bradley Davis is Editor-in-Chief and Audio Producer. He is a candidate for Master's degrees in philosophy and theology at the DSPT and was previously awarded a Fulbright fellowship in Morocco.

William Lombardo is the Politics editor. He is a policy researcher living in Washington, DC and a graduate of Duke University.