Borges's Prophecy

To read this article you need to shut off your screen. Really—dim your brightness to zero or press the lock-screen button.

~

Depending on your inclination to follow instructions you may or may not have done so. And if you did, the screen was (probably) black for only a moment. But I want you to go back, if you would, and shut off your screen (again, if applicable)—gaze at the dark glass for at least a minute.

I imagine, if you took the minute, you saw smears of oil on a dark glassy surface; dust and grease on a computer screen; small, innocent fingerprints on a tablet—you needed to focus on something else, felt too tired to play. With rare exceptions, you certainly found indelible marks on the device left by human flesh and blood, your own or otherwise. These signs, embedded with the unique individuality of a fingerprint (in some cases used to relight the screen), mark the electronification of your body and the humanization of your device. If you looked long enough, a reflection eventually emerged as if in a mirror. A face—only the face you saw isn’t exactly yours anymore. You sell it every morning you wake up. Nearly every time you gaze into this device you sell in exchange for a veiled face increasingly beyond your control. Eventually, you will no longer see anything. And, I must ask, for what price did you sell?

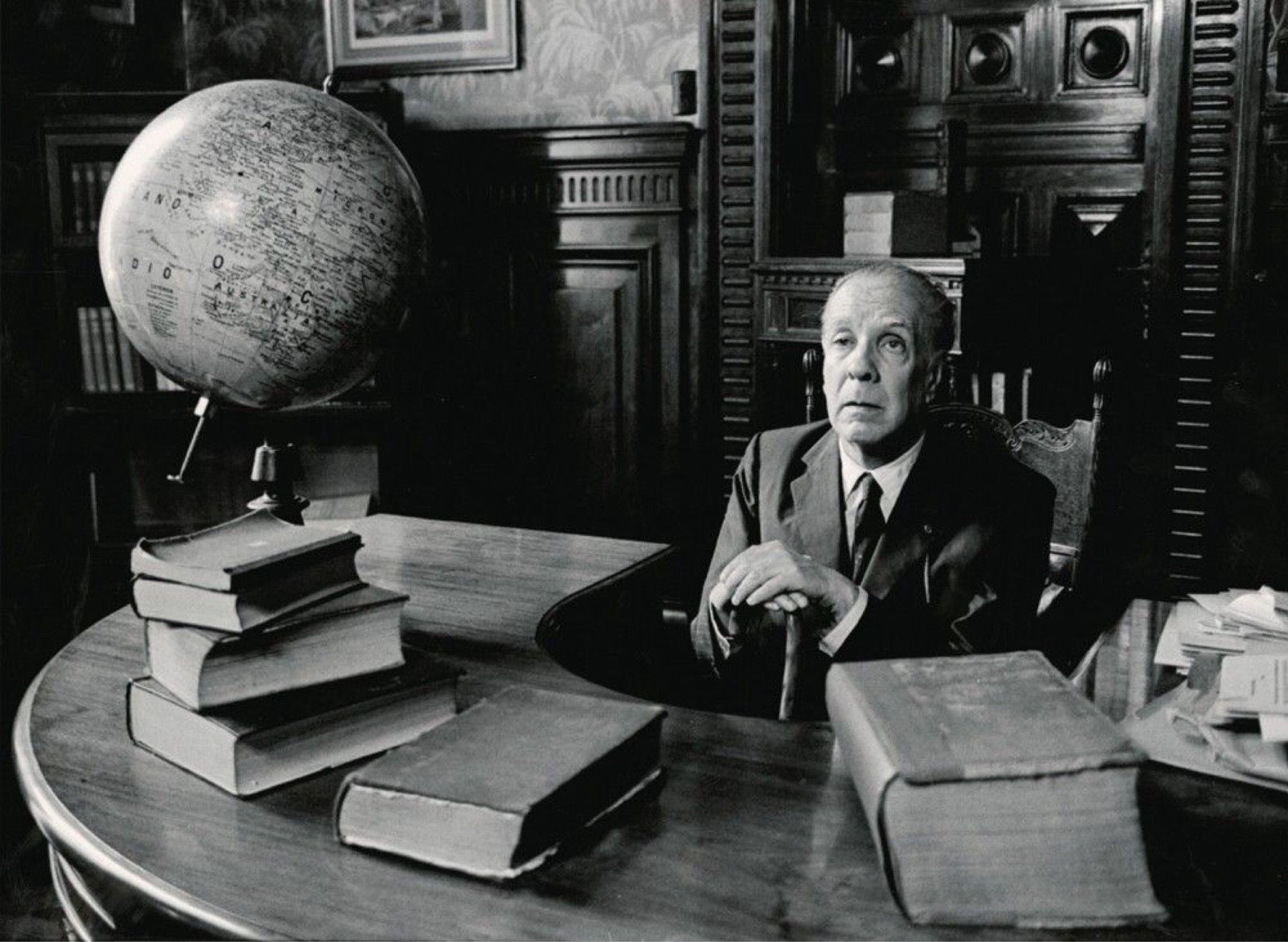

This is a problem quickly approaching universality across the globe, but not without quasi-prophetic forewarning. Nearly 100 years ago, from the Argentinian south, the prescient Jorge Luis Borges portended of such a mirror. In 1935 at 36 years old, Borges published his first short story collection called A Universal History of Infamy which contains the lesser known “The Mirror of Ink” (El espejo de tinta). In the story, the narrator looks back to the Islamic Golden Age and tells of a cruel Sudanese governor named Yāqub the Afflicted, who sought to execute a man and his brother for supposed treason. After the beheading of the former, the latter throws himself at the governor’s feet and pleads for mercy. He explains that, if spared his life, he would show the governor “forms and appearances more marvelous than those of the fanusi jihal, the magic lantern” (74). Intrigued, Yāqub spares the Scheherazadian magician who quickly gathers the necessary materials to prolong his life. After burning some incense and uttering a few incantations, the magician asks the governor to cup his hand in front of him. The magician then pours jet black ink into the cupped hand which stills to form an ebony mirror (place your darkened phone face-up in the palm of your hand). He then tells the governor to look into the newly formed circular mirror and behold a vision. The magician explains that the governor saw “green and peaceful fields and then a horse coming toward him, as graceful as a leopard.” Yāqub, entertained to say the least, then asked to see a heard of perfect horses—one wasn’t good enough—as beautiful as the first, which immediately appear in the mirror’s reflection (an infinite series of cat videos). The hook is immediate, to the point that the sorcerer explains: “my life was safe” (75).

Yāqub craves these visions for many days thereafter, demanding to see “the cities, climes and kingdoms into which this world is divided, the hidden treasures of its center, the ships that sail its seas, its instruments of war and music and surgery, its graceful women, its fixed stars and the planets, the colors taken up by the infidel to paint his abominable images, its minerals and plants with the secrets and virtues which they hold” (75) &c. Thus, day after day, the magician finds himself in the private chambers of the governor, showing him the infinite realities of the world. As time passes on, a veiled Sudanese man begins to emerge in each of the visions with greater frequency. The visions also become less alluring, leaving the governor wanting. The governor waxes numb, requesting visions of greater intensity, even violence. Eventually, he specifically requests a murder. The magician warns the governor to be weary of what he desires. But the counsel falls on deaf ears as the governor revives his original death threat. In strict compliance, the magician brings forth the veiled man to the executioner. In the mirror or ink, the governor watches as the veiled man stretches limb to limb beneath the executioner’s blade. Before the sword falls, however, the governor requests that the man be stripped of everything, especially the veil covering his face: he wants to see the eyes as he dies. The sorcerer, no fool to the situation, advises the governor to refrain, but the governor repeats his death threat. Obedient to the command, the sorcerer unveils the man, revealing the face of none other than Yāqub the Afflicted. Frightened, Yāqub attempts to dispel the ink from his hand, but it’s too late. The magician, now in control, forces Yāqub to watch what he so desperately desired to see. As he beholds his own execution, he feels the immediate, real-world implications of the vision, and falls to his death.

One of the most telling descriptors of the story comes as the narrator notes that the mirror of ink spent so much time in Yāqub’s hand that it left a mark in his skin. The line between the ink and his own body blurred as the ink became his skin and his skin the ink. I would ask you now, dear reader, how your circumstance is different from that of the governor? Blacken your screen and see your own mirror of ink. What kind of mark does your phone leave on your body, on your ability to focus or pay attention to a loved one? In what ways does it stain your hand? Which of the infinite realities of the earth (and, in some cases, the universe) do you demand to see, day in and out, and at the expense of your life? How often do you wake up in your own “bed chambers” and reach to “put on your phone” as if reclaiming a limb? How often do you quietly expect a new YouTube video, a post or an Instagram picture while reloading the page, ever wanting stimulation, and, at times, something violent (fail videos, for example)?

What about the modern magician(s) to whom we freely give of ourselves daily? The narrator makes clear that the magician’s machinery producing the visions depended exclusively on the governor’s attention for survival. The moment the governor lost interest called for the magician’s immediate execution. How is that different from today? The availability of the visions of today—the videos, the pictures, the likes, the comments, &c.—grows at the price of our attention as users and consumers. But the moment we lose interest, Big Tech dies. Our modern magicians know this. They use it to our disadvantage. We know the ad revenue models for Big Tech—just watch The Social Dilemma (2020) or read Adam Alter’s Irresistible (2018). Yet, while we talk about these things with increasing frequency, we aren’t articulating the true cost for which we sell ourselves to these modern mirrors of ink. Remember, the more Yāqub consumed, the stronger the magician became, and the less he (Yāqub) was himself. Eventually, Yāqub completely relinquished his life at the hands of the magician and died in the processes. The mirror of ink turns each who engages with it into the Ouroboros, the self-consuming serpent, that will realize its own destruction, only with little prospects of re-birth. Our modern mirrors of ink, now common among children, deceive us into losing ourselves hour by hour in the infinity of an illusion. And our glut for metaphorical (and literal) violence only seems to grow. The increase in depression, anxiety, stress and disconnectedness—ever more present and ever more pervasive—constitutes a veiled man lingering in the subconscious of the plagued. In some sense, we know we see the veiled man (or woman), and the longer we avoid him, the sharper grows the blade that cuts us from life.

I recognize the paradox in which I write: for you to read this, you must use your own mirror of ink, as, ironically, so must I. In some cases, you arrived at this essay because of the forces that funnel the maximal expenditure of your attention. So, maybe I am the magician. But if I am, allow me to also be a genie in the bottle and grant you one wish: your attention. Darken your screen, only this time don’t come back. Let the ink spill, don’t let it mark your flesh. Instead of reflecting your gaze at glass, artificially lit from behind, steer your eyes to your spouse, your children, your sister, your brother, your mother and father, your neighbor, each infinitely lit from within. Reclaim who you are and the path that takes you where you want to be. If Borges was right, and so far he has been right about a lot (that’s for another day), then at what date will we find that all we have done is forced Big Tech to unveil our faces as we watch ourselves die?

Works Cited

Borges, Jorge Luis. “The Mirror of Ink,” A Universal History of Iniquity.Translated by Andrew Hurley, Penguin Classics, 2004, pp. 74–77.

Laraway, David. Borges and Black Mirror. Palgrave Pivot, 2020.

Scott Raines is currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Kansas studying Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian literatures and holds an M.A. from Brigham Young University. He is a proud husband and father of two—they are his world. He invites you to follow him on Twitter.