The Man Who Climbed Hell and Heaven

Where’s Werner?

The audiobook of Werner Herzog’s new memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All (2023), is 13 hours, 42 minutes, and 41 seconds long. The listener might be pleased, as I was, to hear the filmmaker personally narrate it, milking every word like a Bavarian cow—a rustic practicality the great man notably knows how to do. With Herzog, anything seems possible, and the low becomes high, the high low.

Now in his eighties, Werner Herzog’s artistic life is worthy of a 351-page memoir. While I was at first enthusiastic to listen to Herzog read at such length, I resigned myself to the more traditional experience of the hardback volume. The director’s famously incantatory tone started to become distracting. And, notably, Herzog is charmingly aware of his unique voice's blurring effect.

“There is something authentic and inimitable about speaking one’s own words,” he explains, “that any audience will immediately recognize” but that “no schooled actor or professional speaker can match.” His thickly accented English has given rise to “a number of imitators on the Web who in ‘my’ voice read fairy tales or give advice for living.” Despite these “dozens of imitators,” he’s declared that no one “has really caught my sound.” And that’s true enough. Regarding the ironic resonance between his tone and his work, Herzog notes: “My voice has found a great community of fans, which combined with my view of life asks to be imitated. I am a grateful victim of such satirists.”[1]

As one example, my favorite satirical Herzog has the imitator narrate Where’s Waldo: “Where to begin? (sigh) Top left corner. Hidden somewhere in this noisy, chaotic morass of society is our fellow traveler: Waldo." Even generative AI has gotten in on the game—one in particular pits a fake Werner Herzog to endlessly debate a fake Slavo Zizek.[2]

In this memoir, and his work generally, Herzog’s comic jabs as a writer do outsized damage precisely due to his deadly serious haymakers as an artist. His cinema comes across as deeply conscientious and philosophical, precisely because he is so thoughtful about his role as a storyteller and image-craftsman on a mission: to make new images that help save modern civilized man from himself.

Herzog, as Roger Ebert recounts, “said his duty was to help mankind find new images.” So his films exhibit “many great and vivid” ones. Here are a few from his earlier works:

- “a man standing on a drifting raft, surrounded by gibbering monkeys”

(Aguirre, the Wrath of God, 1972). - “a ski-jumper so good that he overjumps a landing area”

(The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, 1974). - “men deaf and blind from birth, feeling the mystery of a tree”

(Land of Silence and Darkness, 1971). - “a man asleep on the side of a volcano”

(La Soufrière, 1977). - “midgets chasing runaway automobiles”

(Even Dwarfs Started Small, 1970). - “a man standing on an outcropping rock in the middle of a barren sea”

(Heart of Glass, 1976). - “a man hauling a ship up the side of a mountain”

(Fitzcarraldo, 1982).

Nature is violence and wonder. So is cinema. That seems to be the gist.

Across these images, Herzog puts pieces of himself and much more. “We are surrounded by images that are worn out, and I believe that unless we discover new images,” he explains to Ebert, “we will die out. Die like the dinosaurs. And I mean it physically.” While frogs and cows do not need images, “we do.” So just as “Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel for the first time articulated human pathos in a new way that was adequate to the understanding of his time,” Herzog declares, “I am trying to make something that has not been made before.”[3]

Fittingly, the memoir’s epigraph comes from the Epic of Gilgamesh. That choice gestures toward one of Herzog’s skeleton-key motifs and concerns: the wild or natural man contra civilization:

Enkidu heaved a sigh and said:

‘Gilgamesh, the guard in the forest never sleeps.’

Gilgamesh replied: ‘Show me the man

who can climb right up into heaven.[4]

Gilgamesh of course is the oppressive “civilized” king, whereas Enkidu is the wild man the gods create to stop his abuse. It’s civilization and technology versus barbarism and nature—yet while the urban ruler triumphs over the noble savage, these heroes become fast friends who, as brothers-in-arms, slay monsters from both earth and heaven.

Herzog must anticipate this subtlety, since his work—like the penguin he documents leaving its colony for the antarctic interior and almost certain death—constantly suggests the longing for savagery within the soul of the man in the gray flannel suit. What T.S. Eliot says about Baudelaire’s poetry, that “the possibility of damnation” is “an immediate form of salvation” from “the ennui of modern life, because it, at last, gives some significance to living,”[5] is easily adapted to Herzog’s œuvre: his work’s most consistent motif is that the recurring urge for barbarism might just save us as it makes civilization’s pretense significant.

Because we all live through the dulling nullity but so often do not notice it, it takes great art to shake us from torpor and awaken us into insight. Who would think, for example, that the home videos of Timothy Treadwell—the man who famously lived amid bears, only to be later killed by one—sprused with interviews of family and friends, would make for a compelling philosophical dive into just how nature’s call to leave behind civilization can awaken one man’s death drive to also leave behind his humanity? Well, Werner Herzog did, and so he made his documentary, Grizzly Man (2005).

That is Herzog’s sense of artistic duty. “I elevate the spectator,” he writes elsewhere, “to a high level, from which to enter the film. And I, the author of the film, do not let him descend from this height until it is over. Only in this state of sublimity does something deeper become possible, a kind of truth that is the enemy of the merely factual. Ecstatic truth, I call it.”[6]

Calling All Artists: Eat Your Footwear

What an Alpine mountain of fun the audio engineer must have had with Herzog reading in his unleavened tone about his favorite early lead actor—the brilliant, loony, evil Klaus Kinski—or his own 1974 walk from München to Paris to visit a gravely ill friend, not to mention the time he actually ate his own shoe after “losing” a bet he wagered to Errol Morris over whether Morris would finally finish a feature film.

Herzog's relationship with Klaus Kinski is the stuff of legend in cinema history. Kinski, known for his intense and often volatile personality, starred in several of Herzog's films, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982). Both artistic triumph and personal conflict marked the collaboration between the brilliant yet unhinged Kinski and the determined Herzog. Herzog's matter-of-fact tone in recounting these experiences, full of wild tantrums and near-violent confrontations, brings dry humor to the sheer madness of their working relationship.

Despite the chaos, Kinski's performances in Herzog's films are iconic, and Herzog often reflects on their collaboration with a mix of exasperation and admiration, capturing the paradoxical blend of genius and insanity that Kinski embodied. In marked contrast to his greatest actor, Herzog’s own personality tends towards heroic endurance and quiet loyalty, especially when it comes to his friends.

In 1974, upon hearing that his close friend and film historian Lotte Eisner was gravely ill, Herzog undertook an extraordinary pilgrimage. He walked from München to Paris, a journey of over 500 miles, believing that his physical act of devotion could somehow stave off her death. Herzog documented this trek in his diary, later published as Of Walking in Ice (1978). The grueling journey through the winter landscape is a testament to Herzog's determination and belief in the human will's mystical power.

His narration of this event, delivered in his distinctively flat and unwavering voice, underscores his odyssey's profound yet absurd nature, blending personal mythology with a stark, almost surreal sense of purpose. But this sense of purpose proved contagious, both to his fans and his comrades.

So of course when Morris did finish his film—giving us the immortal documentary meditation on death, American banality, and late capitalism, Gates of Heaven (1978)—Herzog cooked and, after adding some onions to it, publicly devoured his shoe in support of his friend. Les Blank even directed a short film about this pedestrian meal, simply titled Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980), a must-watch for any Herzog completist. Herzog's pragmatic tone in narrating this story contrasts sharply with the absurdity of the situation, highlighting his unique blend of stoic determination and willingness to embrace the ridiculous for the sake of art and encouragement.

In effect, Herzog says to us: “Put up or shut up.” And he’s right. Do the thing, or shut up about it. Maybe then you too will one day be worthy of a memoir, in hardback, and a fourteen-hour audiobook, however strange your voice. At the very least, you’ll have tried.

There’s a quality of provocation, pranksterism, and old-fashioned hijinks in Herzog’s work and public persona—unique in the arts, disarming, and absent from today’s sanitized and paranoiac, careerist vibe in “the arts” (yuck). Does anyone remember hijinks, stunts, and unquestionable earnestness? Herzog delivers all of these and more, even through an œuvre that’s ultimately as serious, human, and consequential as anyone’s in any medium—ever.

Herzog is more than a clever man, and cinema will never again see another figure quite like him. His work is akin to phantasmic apparitions of a particular period in history. Happily, he has been extraordinarily prolific. His astoundingly productive range is no small part of his genius and appeal. As his pictures radiate a continental sense of craftsmanship, it’s clear that Herzog has no time for preciousness or pretense. In a word: a man either eats his shoe or doesn’t. You either finish your project and move on to the next one, or you never get started in the first place.

Across his films, interviews, and writing, Werner Herzog’s message to would-be artists is: eat your footwear and make your film. Enough excuses, go and do it yourself, carry the boat over the Peruvian mountain, because money doesn’t make films: will and mania and men and women working at their absolute physical and mental limits do. This inspiring, true, and essential message is for everyone sitting around without realized projects, but with a rising moribund sense of futility. Herzog says to us: stop waiting for permission.[7] There is no better advice for anyone struggling to create yet nevertheless aiming for great art.

Born into the End of the World

Herzog gives his book, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, a rock and roll heavy metal title if there ever was one. Much of it recounts his impoverished, rustic, fatherless, and remote Bavarian childhood in and after World War II. And yet, for its remoteness, it was not without its surprises.

“Some time ago, in some papers,” he writes, “I came upon a postcard from my mother dated September 6, 1942, and written in pencil. The stamp with Adolf Hitler’s likeness was reprinted on it.” It went: “Dear Father… I wanted to tell you that I gave birth last night to a baby boy. He is to be named Werner.”[8] As both his parents went through “de-Nazification,” his father remained bitter at the German defeat and “American barbarism.” Herzog distances himself from all of this without ignoring it.

He even dove into Catholicism as a teenager. When asked in an interview if he believes in God, he explains: “No. Well, I had an intense religious phase when I was 14 or 15. I became a Catholic.” And while “according to the dogma of the Catholic church you cannot leave: you are always baptized because baptism is an indelible mark on your soul,” however, “from my side, I am not a member of the Church, and I am not religious.”[9]

None of us recover from the accident of birth, and one doesn’t need much imagination to see a clear line from Herzog’s soulful childhood amid civilized ruins to the lapsed, yet weirdly spiritual octogenarian author recounting that journey. At the very least, if he believes in a godforsaken nature, he retained in later works that Catholic sense of fallen man’s longings for infinity.

This sensibility comes mostly in hints, like when Herzog explains the illusion produced in Michaelangelo’s Pieta—a 33-year-old Jesus held by a 17-year-old Mary—that “he just wanted to point out an essential truth, or something that resembles more truth” than not. “Because I do not know what truth is, nor do mathematicians,” Herzog explains. “I think only deeply religious people know what it is. So they have an easier life than those who are not religious.”[10]

Beyond these family and childhood stories, Herzog devotes the rest of the memoir to his monumental career. From descriptions of the films he’d like to make to reflections on the films he’s already achieved, Herzog adds to these various but visceral life-and-death scenarios the work has put him in, some earnest philosophical meditations on both the modern world and what he anticipates for the human future … if there is one.

On this note, one of Herzog’s most curious films is Lessons of Darkness (1992). To make the film, he took footage from the burning of Kuwait’s oil fields during the First Gulf War and set it to, of all things, music from classical composers like Wagner’s Das Reinghold, and accompanied by his own narration of Bible passages. He even invented his own apocryphal quotation of Pascal to begin the pseudo-documentary (“the collapse of the stellar universe will occur—like creation—in grandiose splendor”). Such choices illustrate how far as a filmmaker he retains older high cultural habits, conscious of their fragility.

“I try to imagine the world without books like this one,” Herzog writes. “For decades now, people have stopped reading; even university students no longer read. This development is the result of tweets and texts and short videos.” So “what will a world be like with hardly any spoken languages, which are becoming extinct in their profusion and variety? What will a world be like without a profound language of pictures, where my profession no longer exists?” Indeed, “the end is coming.”[11]

Much like he might conclude any one of his documentaries, this self-reflecting metatextual passage is a meditation on death typical of what concerns Herzog. He salutes the reader whose spirit hasn’t been totally fried by the electric, hideously ubiquitous “social” nickelodeon. Now I love a good meme, but we need to be reading, Herzog insists, especially for filmmakers: “Read, read, read, read, read. Those who read own the world; those who immerse themselves in the Internet or watch too much television lose it. If you don’t read, you will never be a filmmaker. Our civilization is suffering profound wounds because of contemporary society's wholesale abandonment of reading.”[12]

Reader beware: if these sorts of meandering, digressing, and philosophical flights annoy the reader, he’s yodeling into the wrong abyss—but he’ll have to read to find out if this one, for all its vocal strangeness, doesn’t yodel back.

All Against All?

On the hardback cover of the memoir, a haggard-looking, ash-covered Herzog, wearing a kind of spacesuit for vulcanologists, looks at the camera like he’s sizing us up—which, of course, is exactly what he is doing, and has done his entire career. The industrial and post-industrial world of man, in and of history, seems to be his Ur-subject.

From the character of Kaspar Hauser (played by Bruno S.) in The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), to the real-life Dieter Dengler in Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997), not to mention a fictional police lieutenant’s (played by Nicholas Cage) “lucky crack pipe” in Bad Lieutenant: Port Call of New Orleans (2009), Herzog concerns himself with humans at the edge of the civilized world. Which any serious person knows by now is not civilized at all, or is only thinly so at the best of times.

And ours are not the best of times. Much like what Herzog explores in his first novel, The Twilight World (2022)—about the imperial Japanese offer, Hiroo Onada, who spent decades resisting surrender in the Philippines[13]—when men break one of this civilization’s porous borders, they strike at a tragic-comic absurdity. For Herzog, they also make for existential contemplation.

To again cite Eliot: Baudelaire’s art showed “the worst that can be said of most of our malefactors, from statesmen to thieves, is that they are not man enough to be damned.”[14] In contrast, Herzog’s protagonists most certainly are! Or at least dare to be so.

If Herzog had not become a filmmaker, he plausibly would have been a writer of novels and travelogs. A sprawling but gripping read, the memoir’s title—again, Every Man for Himself and God Against All—pulls from the German name of his masterpiece, Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle (1974), based on a true story about an early 19th-century foundling, Kaspar Hauser, thrust into the “civilized” world of Nuremberg, one which hatches predictably mixed and finally tragic consequences.

Kaspar’s predicament is our own, cast against all odds, and also bravely played by an often-institutionalized man artistically known only as Bruno S. One place to begin a serious affair with Herzog’s cinema is this film, especially since the choice to give his memoir the same name indicates it holds primacy in Herzog’s mind. In reflection, he seems obsessed with the sort of protagonist who typifies what Herzog sees as Western man’s current crisis. With his memoir, Werner Herzog has, at last, become his own protagonist, and what was mainly tacit in his major films or merely partial in his documentaries is made explicit and full.

Yet this plot twist makes for a great dramatic irony, because one of this memoir’s major points is how collaborative Herzog has been. It becomes easy to lose sight of this fraternity in the face of Herzog’s huge persona and his career that improbably spans seven decades, not to mention his usual choice of unusual, ever-crazed subject matter.

Just as he made that gruesome bet against Errol Morris to encourage completion of his friend’s first film, the seemingly mad German employs these crazy methods to kindly help the people around him. Like his hero Fitzcarraldo’s convoluted storyline—who in Fitzcarraldo (1982) transports a steamship across a Peruvian hill in order to sell enough rubber to build a local opera house—Herzog famously trekked over three weeks of brutal snow from France to Germany, all just to give moral support to his dying friend … and it worked![15]

Herzog makes a point of praising the contribution of others, and it’s not lip service or false modesty: “Among the villains in my films, Klaus Kinski figured from the start. He had a screen presence to match anyone in film history.” Further: “Michael Shannon is another such actor, and Nicolas Cage also is,” who “thinks that Bad Lieutenant is his most extraordinary performance, even ahead of Leaving Las Vegas, for which he won an Oscar. I agree with him.” But “of all the great actors and actresses I have worked with,” Herzog states, “one stands out: Bruno S. His appearance was always rough, as though he slept under bridges even though he had an apartment … He had a depth, a tragedy, and an honesty that I have never seen anywhere else in cinema.”[16]

This generosity is not just in words but deeds. Whenever dangerous stunts are asked of others, he first tests them on himself. This leading by example applies even when it came to the singularly insane project to move the steamship over a mountain—which Herzog actually did, not just to make an authentic film, but also to prove how the simple mechanics of levers and pulleys make great feats possible. As seen in Les Blank’s documentary about the making of Fitzcarraldo, Burden of Dreams (1982), Herzog consistently exuded an iron patience in that production hell, and for all the many crises, was daily tempted by but never gave into despair.

Herzog examines obsessive eccentrics who confront nature’s indifference alone. Yet, even as one of his own protagonists, he renounces isolation. His artistic way of life is in profound ways most un-Herzogian, which probably generates some leverage when it comes to actually realizing his various projects. Here is a man who, tilting at windmills, reveals them to be real, and heroically, artistically strikes them down for us.

The Last Humanist?

Thus Herzog might be one of the few remaining humanists of note, free of malicious irony, earnest and desperate to communicate but never to communicate desperately. If I could take nothing else, I would choose Herzog’s filmography as company on a desert island—the kind of place he’d shoot a film. In fact, it sounds like a nice holiday, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the man decided to make a documentary about it.

From the Kinski films and early features to contemporary sleeper masterpieces, like the sinister Bad Lieutenant, and all the many documentaries, his filmography offers awesome breadth rarely ever matched. An apt comparison might place him in the show business stratosphere with Martin Scorcese—born the same year, just two months apart, both directors straddle the high and low, returning to familiar themes without repeating beats, but always haunted by man’s yearning for heaven and craving for hell.

At this point—for a man who once argued with 1,100 Berlin audience members turned not only angry, but physically hostile all because they saw Lessons of Darkness—Werner Herzog has nothing left to prove. Just like he did in 1992, when he shouted to the crowd of howlers and hecklers: “You're all wrong. This film is good." Later recalling the incident, Herzog says, “There were shouts that I glorified the horror. And I said yeah, ‘Well, Mr. Dante Alighieri did the same in the Inferno and Hieronymus Bosch did it in his paintings. And Goya did it in his paintings.’”[17] Thus, one can presume, Herzog seems himself like Dante, Bosch, and Goya: a poet and painter of the damned.

As most artists, young or old, would sacrifice a leg for a fraction of his impact and longevity, it’s natural that his memoir is an effusive victory lap, and, for those artists especially, another in a long line of Herzogian calls to artistic production. Make your project or stop talking about it. Stop posturing and eat the proverbial shoe.

This memoir will be of interest to anyone who wants to spend some hours in the curiously explosive mind of a genius who achieved the apparently impossible over and over again. If you take the time to listen to Herzog recall this aloud, or read it to yourself with the familiar accent of your own inner ear, you’ll come away knowing more about what it takes to be a working artist striving to preserve the human in a broken civilization.

Even though the friendship with Enkidu civilized Gilgamesh, his friend died, after which the king strove the seas and scoured the deep for the secret to immortality. Finding none, Gilgamesh came home a wisened man and gentler ruler. He no longer could grasp the deep, so he looked above in wonder. Herzog offers such depths and heights to the reader.

So why delay? Get on with it. Do the damn thing now—it might just save you. Read the memoir. Make your art. Eat your shoe.

Werner Herzog, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, trans. Michael Hofman (New York: Penguin, 2023), 289, 293. ↩︎

As one example of Herzog’s argument:

“I have very deep religious feelings. If I say that Columbus was sent by God, then I really mean it. It's not a figure of speech. I think there is a place for this type of compulsion, like a divine command. I would never deny that. Even my mother, who was an agnostic, once said to me that she was convinced that she came into this world to bear me. Wow! That's pretty strong. It's a very strong feeling. I have it too and I feel that sometimes it's not freedom that counts but something else, a certain compulsion. I don’t know how to describe it.” (Accessed 30 May 2024) ↩︎From Roger Ebert’s 1982 interview with Herzog. It is worth citing at length:

Ebert: “Do you feel you have a personal mission to fulfill?”

Herzog: “If you say 'mission’, it sounds a little heavy. I would say 'duty' or 'purpose.' When I start a new film, I am a good soldier. I do not complain, I will hold the outpost even if it is already given up. Of course I want to win the battle. I see each film more like a high duty that I have."

Ebert: “Is your duty to the film, or does the film itself fulfill a duty to mankind?”

Then Ebert notes: “Herzog nodded solemnly. He said his duty was to help mankind find new images, and, indeed, in his films there are many great and vivid images: a man standing on a drifting raft, surrounded by gibbering monkeys; a ski-jumper so good that he overjumps a landing area; men deaf and blind from birth, feeling the mystery of a tree; a man asleep on the side of a volcano; midgets chasing runaway automobiles; a man standing on an outcropping rock in the middle of a barren sea; a man hauling a ship up the side of a mountain.”

Herzog: "We do not have adequate images for our kind of civilization. What are we to look at? The ads at the travel agent's of the Grand Canyon? We are surrounded by images that are worn out, and I believe that unless we discover new images, we will die out. Die like the dinosaurs. And I mean it physically. Frogs do not apparently need images, and cows do not need them, either. But we do. Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel for the first time articulated human pathos in a new way that was adequate to the understanding of his time. I am not looking to make films in which actors stand around and say words that some screenwriter has thought were clever. That is why I use midgets, and a man who spent twenty-four years in prisons and asylums (Bruno S., the hero of Stroszek) and the deaf and blind, and why I shoot with actors who are under hypnosis, for example. I am trying to make something that has not been made before."

Roger Ebert, “Werner Herzog” (1982), Awake in the Dark: Reviews, Essays, and Interviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006, 2017): 59-63, 61-62. (Edited for style and clarity.) ↩︎Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet II, quoted in Herzog, ibid, epigraph. ↩︎

T.S. Eliot, “Baudelaire” (1930), Selected Prose, ed. Frank Kermode (New York: Farris, Strauss, and Giroux, 1975): 231-236, 235. ↩︎

Werner Herzog, “On the Absolute, the Sublime, and Ecstatic Truth,” Arion 17.3 (Winter 2010), 1, online. ↩︎

Herzog’s advice to Errol Morris, as recounted at the shoe’s public eating, is prescient:

“So I said to him: “You’re a man who should make films and and you are gonna do that film now.” And he said to me: “Well, I don't have any money and nobody will give me money.” So I said, “Money doesn't make films. Just do it and take the initiative.” Then I said. “I'm gonna eat my shoes if you finish that one.” That's a moment now. … I didn't mean to eat this shoe in public. I intended to eat it in the restaurant, but…it should be an encouragement for all of you who want to make films and who are just scared to start and who haven't got the guts. So you can follow a good example. … He borrowed money everywhere and he stole. I don't know how he did it, but that's a way to do it. If you want to do a film, steal a camera, steal raw stock, sneak into a lab and do it.”

Herzog quoted in Les Miller’s Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980). ↩︎Herzog, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, ibid, 6. ↩︎

Herzog quoted in Huw Spanner, “Depth of Field: Werner Herzog,” High Profiles, 27 March 2012, online. ↩︎

Werner Herzog, Interview with Eric Weinstein, The Portal, Episode 3: “The Outlaw as Revelator,” 31 July 2019, online. ↩︎

Herzog, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, ibid, 335. ↩︎

Werner Herzog, Interview at Stanford University (2016), online. ↩︎

Werner Herzog, The Twilight World, trans. Michael Hofmann (New York: Penguin, 2023). ↩︎

T.S. Eliot, “Baudelaire,” ibid, 235. ↩︎

His friend was the film historian Lottne H. Eisner (1896-1983), the trek went from 23 November to 14 December 1974, and his diary from that time was later published in book form. Herzog said of hearing the bad news: “I said that this must not be, not at this time, German cinema could not do without her now, we would not permit her death. I took a jacket, a compass, and a duffel bag with the necessities. My boots were so solid and new that I had confidence in them. I set off on the most direct route to Paris, in full faith, believing that she would stay alive if I came on foot.” He continues: “Our Eisner mustn’t die, she will not die, I won’t permit it. She is not dying now because she isn’t dying. Not now, no, she is not allowed to. My steps are firm. And now the earth trembles. When I move, a buffalo moves. When I rest, a mountain reposes. … When I’m in Paris she will be alive.”

Werner Herzog, “Foreword” & “Saturday 23 November 1974,” Of Walking In Ice (1978), trans. Martje Herzog and Alan Greenberg, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), online. ↩︎Werner Herzog, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, ibid, 6. ↩︎

“I had these difficulties quite often in my own country. The last big thing was Lessons of Darkness, which showed at the Berlin Film Festival at the forum, International Forum, and there were something like 1,100 peoples, and they howled in disgust and shouted me down, and spat at me. And it was just stunning and I thought it was a good film. I stood there and I said, "You're all wrong. This film is good." And there were shouts that I glorified the horror. And I said yeah, "Well, Mr. Dante Alighieri did the same in the Inferno and Hieronymus Bosch did it in his paintings. And Goya did it in his paintings. So, what?" Then, Gregor, the festival director, he told me, "Can we get out here backstage?" I said, "No. I'm going to walk down all this aisle." And I walked down. Of course, I had even agitated them more and they spat at me, and threw things at me, and howl, 1,100 people in howling disgust. Look, it's truly a fine film. I swear to God.”

Werner Herzon, Interview by Roger Ebert, 30 April 1999, online. ↩︎

Kevin Kautzman is a playwright, screenwriter, co-host of the podcast, “Art of Darkness,” and co-founder of Bad Mouth Theatre Company. Holding an MFA from UT Austin, where he was a fellow at the Michener Center for Writers, he can be found on X and his website.

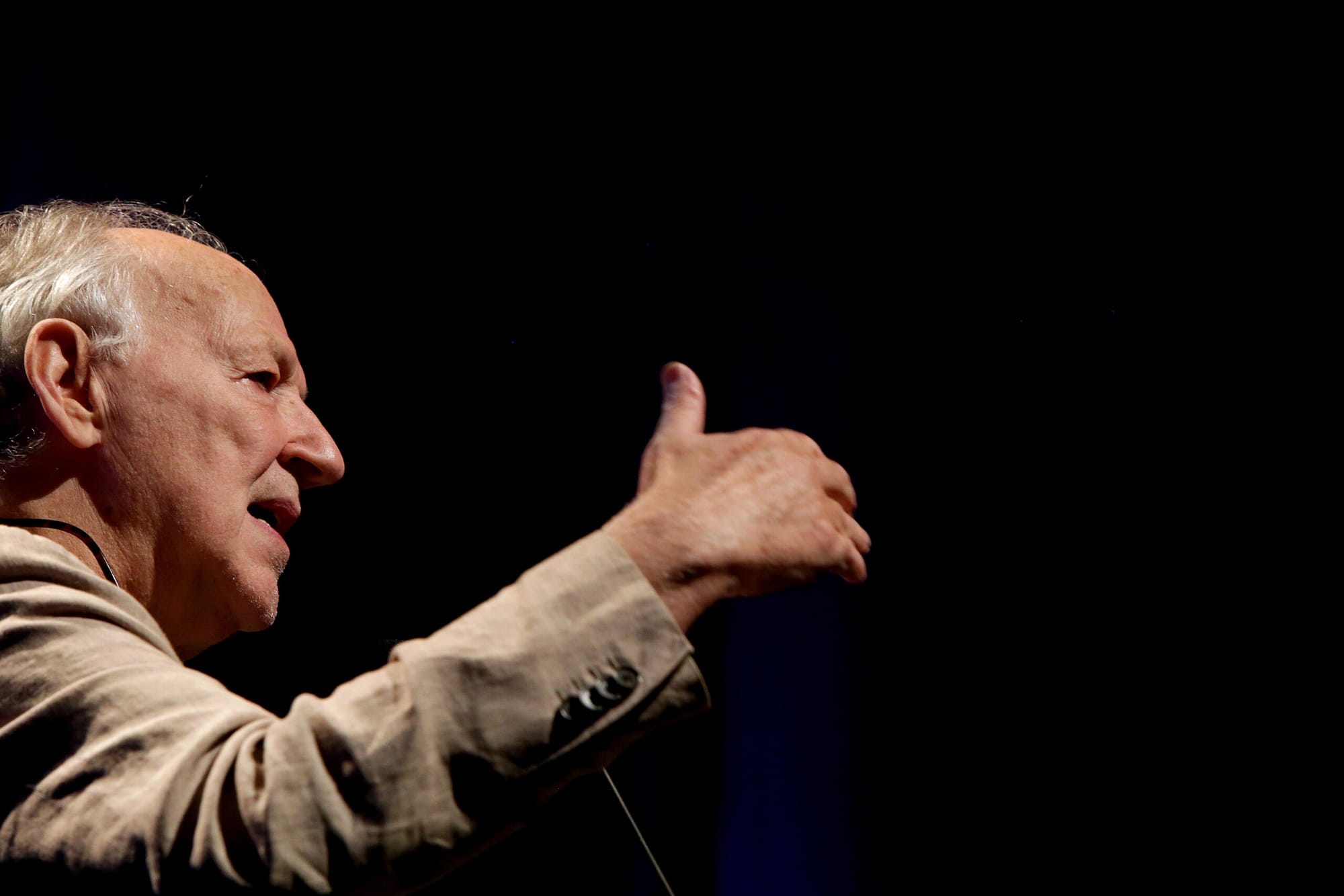

*Featured image: Werner Herzog in photo (2000) by Fronteiras do Pensamento via Wikimedia Commons.