Right and Wrong Lessons from the Kingfish

The waves of populism crashing upon America’s shores have resurrected the cultus of Louisiana Senator Huey P. Long, who has become the apple in the eye of both left-wing and right-wing populists striving to revitalize the American state, resurrect American Labor, and bring back domestic manufacturing. Both the left-wing Current Affairs and right-wing American Greatness have published pieces admiring the Kingfish—but the New Right’s interest in Long is particularly striking.[1] Why has this small but energetic crowd taken such a shine to Long?

To explain why so many so-called national conservatives draw the wrong lessons from Long’s legacy, it’s first important to touch on the man himself. Huey Long was born in 1893 to a middle-class family in Winnfield Parish, Louisiana. As soon as young Huey could walk he exhibited the qualities of a young Napoleon or Augustus. In textbooks he’d write his name as the “Hon. Huey P. Long.”[2] He disobeyed rules with ease and made up his own. The old men of Winnfeld (whom young Huey would often “advise” on what political opinions to adopt or what moves to make during games of checkers at the town general store) soon took to dubbing him “that smart-aleck kid.” Young Long embodied the spirit of Hannibal; if he could not find a way to get what he wanted, he would make one.

Long’s confidence was matched by a peerless political genius. He was unlike other Southern populists: most, ranging from South Carolina’s Pitchfork Ben Tillman to Mississippi’s Theodore Bilbo, would be swept into office by channeling the discontent of their states’ poor whites. But the conservative Bourbon Democrats in the state house and their backing financial interests expertly leveraged parliamentary procedure to isolate and contain the populists, leaving them as do-nothings who spent the rest of their tenure as figureheads with a penchant for race-baiting instead of legislating.

Long was an exception. He had a prodigious intellect and an encyclopedic knowledge of procedure, which he obeyed or broke depending on his convenience. During legislative sessions, the normally in-control Bourbons desperately tried to keep up as Long sprinted down the aisles barking orders to subordinates and commanding followers to deploy archaic procedures to slow down or speed up the process depending on his need. His control of the floor allowed him to pass reform after reform, earning him the adoration of the poor and the impotent rage of his enemies. Huey’s bark was backed up by his bite through his massive statewide political machine, which doled out favors to allies and punishments to opponents through jobs and political appointments. His organization was a massive operation manned by political hacks, local sheriffs, small businessmen, and provincial farmers which guaranteed Long political power the heights of which no Southern populist had achieved before him.

Long’s genius for politics, law, and oratory impressed many. As a young lawyer and railroad commissioner, Long argued a case in front of the Supreme Court, and was described as one of the finest legal minds Chief Justice William Howard Taft had ever met.

This essay’s aim, however, is not to recount Huey Long’s achievements, which others have covered sufficiently. The aim is to understand why one would revive his political legacy and what lessons are proper to take away from the Kingfish’s career.

It is easy to admire Long. In the words of American Greatness’s Pedro Gonzalez, “The Kingfish actually was what Donald Trump only pretended to be.”[3] For the self-identifying Longist there’s an aching for political possibility. What is more wondrous of possibility than a champion for the poor, a crusader against the rich? Long was a homegrown southerner who dressed like the people, talked like the people, and, most importantly, embodied the values of the people. His impenetrable southern drawl and homespun tales from childhood either charmed or alienated every Eastern Establishment elite who crossed paths with him. He was a man whom President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s mother would refer to as “that awful man sitting on my son’s right” during a very awkward dinner with the President.[4] Long was a colorful character who nonetheless had the interests of the people at heart.

Best of all is Huey’s signature ambition: the Share Our Wealth program, a nationwide political organization that called for capping fortunes at $100 million, guaranteeing every family an annual income of $2000 with old-age pensions and American workers a 30-hour work week and four-week vacation. This is a social democratic platform far more radical than anything even proposed by Bernie Sanders. Long’s legacy evinces the perfect synthesis of economic progressivism and cultural conservatism that current-day populists hope to tap into.

But why stop at Long? Yes, Long’s Share Our Wealth program was radical. But why does either the left-wing or right-wing populist stop just short of, say, industrial democracy and take the extra step of transferring ownership of the factories from the bosses to the workers? Why reach to the sky when you can aim for the stars?

The answer is that the target of populists isn’t the system itself, but its excesses. For populists, the system is not at fault, but instead the fault of greedy bad actors who’ve bent the system’s rules to benefit the few over the many. The allure of Huey’s platform is to retake the system from the avaricious bankers of Wall Street and give it back to the wholesome folks on Main Street. Huey, in other words, wished to save capitalism from itself.

This is a claim Huey himself acknowledged. As T. Harry Williams recounts in his biography Huey Long, Long staunchly disassociated himself from the socialists, a rising power within Depression-era America. While the socialists wanted government ownership of wealth, “he, on the contrary, would retain the profit motive” and only trim the worst excesses of the system.[5] There wouldn’t be fewer millionaires, he claimed, but more. Long wished merely to extend more opportunities to ordinary folk while saving the business magnates from themselves.

How effective was this program? Sadly we’ll never find out. Huey was felled by an assassin’s bullet in the Louisiana state Capitol on September 8, 1935. The 7.5 million-strong national organization he built quickly fell apart without its chief. Refracted through the political achievement of his urbane nemesis, Huey’s most popular policies such as Social Security would end up in FDR’s New Deal program.

There are important lessons to be drawn here though; lessons the Longists have neglected. The first being the flaw of the personalist Caudillo-styled leader. There is no doubt that Huey was a political genius. But this political genius, along with his whole movement, died that autumn night in Baton Rouge. While building the movement around himself afforded Long an incredible amount of power, the machine immediately collapsed into petty factionalism the moment its leader passed on. It is hardly surprising that Long could not buck a trend seen from Alexander and the Diadochi to Clovis and his sons.

Contrast this with the early-twentieth century Labor movement. Even despite the US State jailing, exiling, and executing hundreds of the movement’s most militant leaders, including Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene Debs and IWW leader Bill Haywood, the movement was able to continue on without them, albeit weaker, because its strength resided primarily among the people—not in the organization’s leadership. As Debs himself would say, “Socialists are not on the alert for some mythical Moses to lead them into a fabled promised land, nor do they expect any so-called ‘great man’ to sacrifice himself upon the altar of the country for their salvation. They have made up their minds to be their own leaders and to save themselves. They know that persons have deceived them and will again, so they put their trust in principles, knowing that these will not betray them.”[6] Movements whose engines are the people and the principles they’re united around last longer than those based around personality alone.

Even the Civil Rights movement managed to continue on without the towering presences of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. because the church and community were the movement’s center of gravity. While the engine of the Labor movement was the people, the engine of the Share Our Wealth movement was personality—Huey’s personality. The results of which showed themselves after his passing. For without the Kingfish’s presence, his kingdom—and understand that it was a kingdom—was quickly subsumed and divided up by feuding elites in Louisiana while his millions-strong Share Our Wealth organization disintegrated. Those who deify Long would be wise to understand what happens when you place your hopes into one man instead of the people. While the Labor movement outlived its principal leaders, the Share Our Wealth movement collapsed the moment its leader took a wrong turn in a hallway somewhere in Baton Rouge.

The second lesson is that populists must understand the workings of capitalism. Huey Long is not the first left-wing social democrat of the west. Out of the tremendous class struggles that took place in America and Europe arose great social democracies more in line with Huey’s vision. Huey and the social democrats, despite vast cultural differences, both aimed for a class collaborationist society wherein workers and bosses worked to preserve the common good; they wished to preserve the profit motive of capitalism but limit its excesses.

Today these Western social democracies, whose policies Huey championed so fiercely, are in dire shape. The New Deal lasted only three decades before the profitability crisis of the 1970s, at which point the forces of Big Business—allied in part with the small business class that constituted the Goldwater and Reagan coalitions—dismantled it to preserve profitability by moving manufacturing overseas and financializing its corporate structures. The labor movement, rendered inert by right-to-work laws and the Second Red Scare decades earlier, could only stand back and watch as the concessions won with blood by the workers were yanked one by one out of their hands by the forces of capital. Given that the New Deal, a system hated by the business elite despite its relatively moderate policy, was so quickly decimated, would Huey’s Share Our Wealth program really have lasted longer?

Some national conservatives and even left-wing reformers may say yes, it would. One might say that if Huey would’ve cut the knees of Morgan and Rockefeller and Mellon out from under them, then maybe it would’ve been harder for the capitalist class to regroup and outmaneuver labor. If only Huey could have made capitalism work as intended, for the people, then things would have ended differently.

But in the words of Bill Haywood, so long as there remains a system where for “every dollar that the boss did not work for, one of us worked for a dollar [we] did not get,” these “radical” social democracies will stand on sinking sand. One cannot reform away the profit motive of capitalism. So long as the profit motive is preserved, the concentration of wealth, the further immiseration of the worker, and the expropriation of the small capitalist by the large capitalist will be preserved as well.

The excesses of capitalism cannot be limited so long as the profit motive remains untouched. Neither Huey nor his political adversary Franklin D. Roosevelt, for all their genius, could reform away the social forces which arise from this unending hunger of profit inherent in capitalism. The social forces unleashed by capitalism erode all barriers to profit: whether that be a Deccan village under the mid-nineteenth century British Raj, a 2018 Labor Party MP desperately defending the NHS from privatization, or a 1930s Southern populist whose one-man movement was cut short by a well-aimed bullet.

The material conditions of modern day America are far different from Huey’s America. In Huey’s America, there existed a militant labor movement. In our America, the labor movement is crippled and small. In Huey’s America, there existed the threat of Global Communism in the vessel of the USSR. In our America, capitalism is the unquestioned hegemon over the world. It is no longer a fight between a somewhat autarkic-communist Soviet Union and a capitalistic United States; it is instead a duel between a state-capitalist China and a laissez faire United States, both of whose economies are completely interconnected with the other’s. The fight for supremacy between the two is comparable only to a knife fight between two siamese twins. A modern day Long could hem and haw about bringing manufacturing back from China to give Americans good jobs again, and he could command corporations to cease using the crutch of financialization to prop up profitability and go back to making things. But outsourcing and financialization are merely the twin children of a deeper cause: the declining rate of profitability. We rely so completely on China not because of a few bad actors enslaved to avarice, but instead because of a decades-long war by the American capitalist class against the great stagnation which has befallen the global economy since the 1970s. And even in spite of how lean and mean these firms have become, shedding all unnecessary productive units, financializing to a fault, and cutting costs by relying on arms-length third-party manufacturers: they are still just treading water.[7]

The wealth transfer necessary for these firms to even consider coming back en masse would be unprecedented in the history of capitalism. Convincing Nike to transfer manufacturing back to the United States—where they have to pay 1300% more in wages and have to mind actual safety and labor regulations unlike in Bangladesh or Thailand—would require both ludicrous subsidies and prohibitively higher prices. A Longist would have to dedicate so much in wealth transfers for these firms to come back that there won’t be anything left for labor: those social security checks, those pensions, those yearly checks cut to every American family would be impossible under a regime dedicated to making up the profitability difference between manufacturing firms operating in Vietnam and Laos versus Mississippi and Arizona. Thus, the Longist, formerly a man of the people, must resign himself to working within a system built around the preservation of the profit motive. The man of the people no more. The populists, whether they be in the mold of Trump or Sanders, are therefore faced with the following paradox: the wealth required to bring manufacturing companies back over is such that there could not possibly be enough left over for the Longist programs the populists admire so dearly.

Systems make fools of heroes. Lyndon B. Johnson, the “Master of the Senate,” also accomplished much during his time in power. But once his guile and political genius died out with the light in his eyes, Johnson’s accomplishments, such as his policies to promote Black homeownership, were systematically deconstructed and sold for parts to sate the real estate industry’s unending need for profit. Huey Long, who could’ve been America’s Caudillo, would most likely have fallen to the same fate. You always lose when you play by the house’s rules. The only winning move is not to play.

It is not a few greedy men who have dragged us into this world of terminal decline, dysfunction, and decadence. There are no villains to defeat, no cabal of Standard Oil executives and railroad barons. The profit motive precedes the plutocrat. The system forces all to submit to its will. A man can be good. But if he’s a boss, he cannot act according to virtue, but rather must act according to his bottom line—the welfare of his workers is subordinate to profit. Thus, in capitalism it is not good versus evil. It isn’t even bad boss versus good worker. It is simply boss versus worker. There is no room for morality within the class antagonism of capitalism—only profit.

One day, as Huey and a friend were walking down a New York City street, he stopped to point out his favorite book in a shop window: The Count of Monte Cristo. Huey announced he’d buy the book and asked the friend if he ever read it, to which the friend responded that he did, but not since he was a boy. “I read it then too,” Huey said, “But I read it every year. That man in that book knew how to hate and until you learn how to hate you’ll never get anywhere in this world.”[8] Huey’s hate achieved much yet fell tragically short. Perhaps he’d have been better served reading Rosa Luxembourg’s The Crisis in German Social Democracy, wherein he might’ve found the dichotomy “socialism or barbarism.” The Kingfish rejected socialism. Long and his movement met a tragic, barbaric end.

Jay Swanson, “Huey Long and the Power of Populism,” Current Affairs and Pedro Gonzalez, “The Long Shot”, American Greatness. ↩︎

. Harry Williams, Huey Long, (New York: Vintage, 1981), 35. ↩︎

Gonzalez, “The Long Shot.” ↩︎

Williams, Huey Long, 602. ↩︎

Williams, Huey Long, 694. ↩︎

Eugene Debs, The Socialist Party’s Appeal for 1904, 6. ↩︎

Elaborating further upon the decline in the general rate of profit and its relationship to outsourcing and financialization since the 70s is beyond the scope of this essay. For further reading, I recommend John Smith’s Imperialism, specifically Chapter 10: All Roads Lead Into The Crisis. ↩︎

Williams, Huey Long, 34. ↩︎

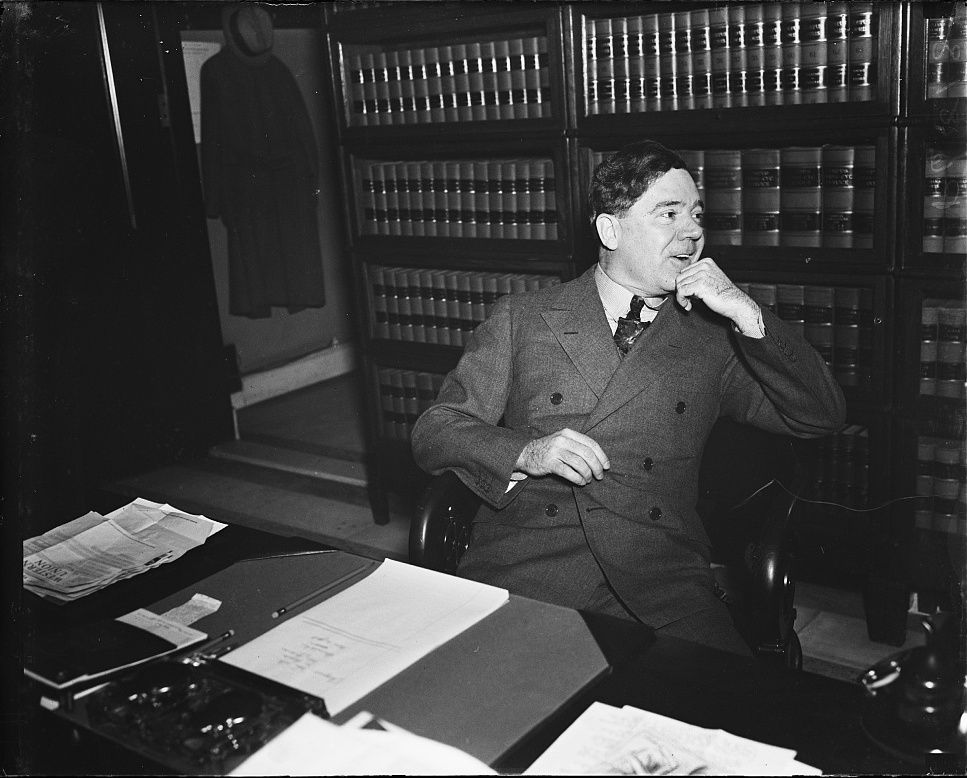

Featured image: Huey P. Long in his office in photo (1935) by Harris & Ewing via Library of Congress.

Julian Assele writes from Washington, D.C. He invites you to follow him on Twitter.