It increasingly seems like a touch of eccentricity is necessary for aspiring political leaders to attain electoral success. For all the talk of “vibes” in the 2024 election, Donald Trump has managed to stage an unprecedented comeback on the sheer force of his personality alone. And yet, in doing so, he is only one member of a much longer list of unique, anti-establishmentarian, and easily meme-able candidates recently elected to (if not out of) high office: El Salvador’s “world’s coolest dictator” and Bitcoin enthusiast Nayib Bukele, former Brazilian President and honorary Florida Man Jair Bolsonaro, the mystical Mexican President Obrador, former comedian Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the clownish Boris Johnson, and Emmanuel Macron’s pivot to a sleek nationalism. Argentina’s Javier Milei—known locally as el Peluca (“The Wig”)—has, for example, drawn upon his sideburns, esoteric personal habits, and anarcho-capitalist edgelording to tap into some lingering public sentiment.

It’s no coincidence that all these men are self-styled populists whose personalities help to both generate attention and cement their image as outsiders. In many ways, their unflinching weirdness and breaking of conventional norms of “electability” serve as visibly biting satire of the underlying arbitrary and artificial nature of the supposed standards for how political leaders ought to act. Given their prior roles in the entertainment industry, for example, both Trump and Zelensky’s subsequent leadership during national crises reads like a postmodern novel or some twisted vision of Neil Postman. Even so, Trump, Bolsonaro, and Milei supporters seem to take delight in challenging elites’ conventional wisdom that each of their countries’ voters could not possibly elect a person like that.

These leaders are clearly a creation of the social media age. Their theatrical, vaudeville-esque approach to politics is not only better suited to the YouTube or TikTok short, but is frankly much more entertaining for current tastes than the alternative Lincoln–Douglas or Kennedy–Nixon debates that once attracted a much less distracted populace. Nevertheless, the repeated, continued success of this kind of leadership suggests it’s more than just a recurring campaign strategy.

During their leader’s years out of office, the Republicans, for example, had flailed and still continue to fail to deduce a clear path toward a “Trumpism without Trump.” It is now quite difficult (if not a tad bit embarrassing) to recollect, at the President’s lowest point, the genuine elite conservative enthusiasm that surrounded a figure like Gov. Ron DeSantis for a time. Much like any 2015–2016 alternative GOP candidates to Trump, DeSantis and the other 2023 challengers lacked the same confidence and increasingly necessary personality. This was the case even though, according to conventional or ‘expert’ opinion, DeSantis was more or less the ideal candidate and would, it seems, have made the better president, given his record in Florida.

Even with its genuine accomplishments, the first Trump administration was chaotic and inefficient. This kind of leadership is also given difficulties by critics who deem it contrary to what they see as the procedures of a constitutional democracy. In this view, the institutions matter most of all, and the detrimental effect of executives like Trump undermines public trust in things such as bureaucratic neutrality, expert opinion, and procedural integrity, all in the name of an overriding loyalty to their central, personal authority. And yet the former President continues to retain a commanding and loyal following among partisans, and beyond, if winning the popular vote has any larger significance.

Likewise, the question of whether or not Sen. J.D. Vance—Trump’s presumptive successor and current enforcer—can realize the amorphousness of the Trump era into something more enduring seems equally dubious. Although the running mate is quite certainly serious about policy, he has more often than not leaned into theatrics and memes. And yet, even while it could be suggested that Trump has outsourced—perhaps even transferred—his 2016-style populism to Vance and other surrogates old and new, this pivot is still always done in reference to the once and future president.

Indeed, the apparent importance of striking personality to successful leadership is driven by a more fundamental crisis of political authority and legitimacy. These charismatic leaders and their inspired movements continue to find a large degree of success in the western world, both in and out of power, because they are charismatic, even if they typically fail to accomplish any deep institutional policy changes. Such an explanation is, of course, a contested, vague, and often shallow way to describe political leaders too reminiscent of self-improvement books or of cable news pundits.

However, if we consider the concept of charisma’s origin in Max Weber, one sees that these leaders continue to emerge and retain influence because their personalities, like the mystics and itinerant preachers of old, serve as a popular foundation on which to recreate or revitalize a broader political order. Charisma is a symptom of (and an attempted solution to) the near-total lack of trust in our institutions caused by a primal dissatisfaction with the prevailing liberal status quo.

In Weber’s thought, charisma is the broader social force that maintains the legitimacy and authority of intentionally-constructed but eroding political institutions. They break down when their organizational purpose seems no longer obvious or credible. In the absence of binding traditional authority, all social forms are created and sustained by their relationship to specific individuals who have been recognized by others to have a special status or set of capacities.

Importantly, Weber borrowed a term that had until that point been used predominantly in religious settings. “Charisma” was meant to convey a more divine or mystical power, as well as a deep contact with the root of existence, the sacred, or the cosmic order. His contemporary readers, for example, would certainly have been familiar with Rudolph Sohm’s exposition of the concept in his 1892 work, Kirchenrecht (Canon Law), which contrasted the charisma of the early Christian church's endowment of the Holy Spirit with the legalism and bureaucracy that grew under later medieval Roman Catholicism.

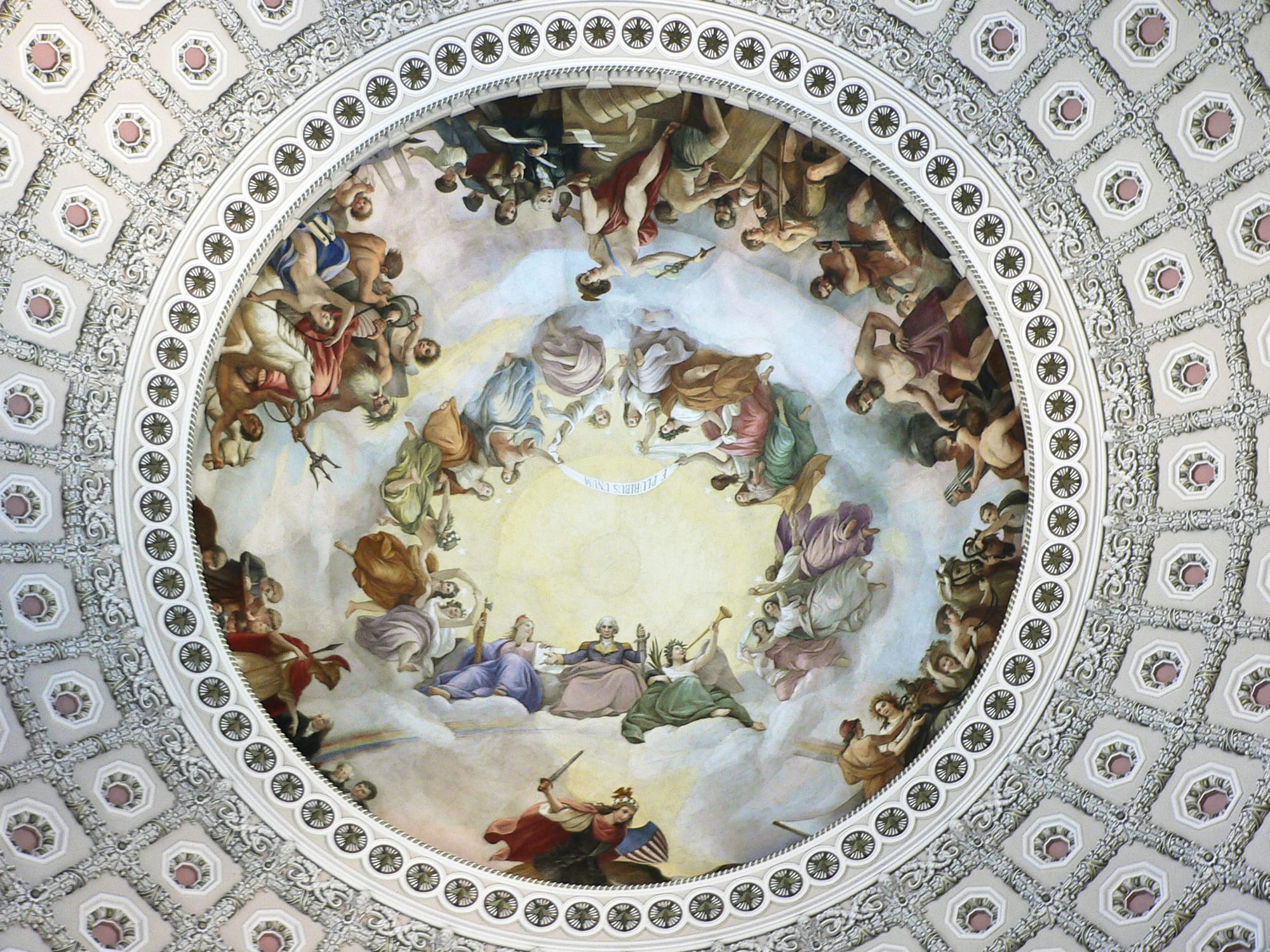

This context frames the setting in which both ancient and modern forms of social legitimacy have been maintained and contested. It is the reason why nearly all mythic civic founders are the children of gods, and it is the source of the biblical narrative’s fixation on the lineage of its major figures. More recently, it can be seen in the way in which Constantino Brumidi’s fresco the Apotheosis of Washington (1865) elevates the first president of the United States to the status of quasi-divinity at the architectural center of the Republic in the dome of the Capitol Hill rotunda—despite the likely derision that would have come from the founding father himself. In fact, this civic worship is an overlooked aspect of the debates that continue to rage about how we publicly present our historical figures, for statues of deceased individuals are not objective reflections of the past as much as they are religious icons.

Applied to politics, charisma is therefore meant to convey something more fundamental to the core values, principles, and meanings that frame and legitimize a constitutional order. It is not about the rational, ends-oriented justification of routine policymaking, but the personal and social meaning derived from the process. But while charisma is shaped by a more intense and personal nature, the test of any secure and long-standing social order depends on the effective transfer of charisma from specific individuals to a more secure institutional form. At a certain point, Sparta should no longer need Lycurgus as an active leader, if it can live by his laws alone. The same applies to Fransiscans and St. Francis, or the American founding and George Washington. Yet all these men continued to be revered or even worshipped by the communities they founded.

Within Weber’s thought, there is still a sense that the engaging and mobilizing element of charisma is gradually lost. Over time, social institutions lose any sense of their fundamental meaning as they become more means-oriented and increasingly justify their authority on technocratic expertise as well as unchallenged platitudes. The regime, through its bureaucracy, acts for the sake of itself. This state becomes stale and oppressive, not because it is necessarily anti-participatory, but more so because it places a claim to objectivity above the more fundamental—and deeply creative—human drive to secure meaning, belonging, and self-recognition. Ultimately, this tension between the continual pursuit of meaning and the need for a secure order helps drive social development, but which a dead bureaucratic culture would fail to channel.

Seen through this lens, the ongoing emergence of populist leaders indicates that much of the West has detached itself from its charismatic linkages. It has gone too far towards an overt, stifling rationalization and technocratic form of governance. This type of structure operates according to a worn out set of policy goals pursued for their own sake, independent of their more historic relationship to what it means for man to be the political animal—the more profound reasons why we human beings structure the political world the way we do.

Because it suits the interests of their permanent ruling class, western governments—regardless of the party in power—continue to advance the same policy goals of further economic growth and corporate consolidation, state oversight of the private sphere, substantive immigration, and identity-driven social justice. All the while we have ceased to ask why we pursue these goals at all, as many people have not only lost touch with their apparent value, but continue to face challenges that still go unaddressed: uneven economic growth, material insecurity, atomization, addiction and suicide, and ever-declining social trust.

Such are the grounds for the reassertion of charisma. When people are placed in ambiguous, undefined, and conflicting situations, they search for alternative foundations to not only reassure themselves of their status, but more importantly find a deeper tethering to a more profound source of meaningful political identity.

But charisma for Weber is also innately destructive as it, paradoxically, requires a certain degree of sacrilege. In seeking after—if not creating—something more fundamental, leaders are mandated to undermine the broken status quo by questioning what is treated as sacred by the society at the time. Delight is thereby found in forms of derangement or deviance as a way to draw out the nonessential and vulgar. And, ultimately, sufficiently distinctive leaders are endowed with a special calling by their followers to discover it.

It is this urge, rather than some coherent set of political doctrines, that fuels the mischievous and inflammatory tone of much of today’s politics, most notably the online “dissident” or “alt” right that supports the archetype of this kind of leader. For the systematic dismantling of existing orthodoxies—that is, owning the libs—is precisely the point. And yet, what remains unresolved is exactly how this account shapes our understanding of political engagement’s association with Truth. How, after having supposedly dismantled the regime that came before it, is the force of charisma supposed to rebuild a new foundation?

This is a practical question as much as it is a deeply philosophical one. Recent experience shows that populists not only struggle to appoint credible successors, but also to fully articulate the whats and hows of real power. In the United States, for example, much of the promise of the first Trump administration was quickly domesticated. After all, that first team not only failed to adjust to a regime that has been intentionally designed to contain substantive change, but which also filled in the vacuous spaces of Trump’s rhetoric with conventional policy prescriptions. It is no coincidence that Trump’s most significant domestic policy successes were cutting taxes and appointing judges. Likewise, in weaker states, populists only seem to promise a succession of short-lived regimes.

Charismatic leadership, it seems, cannot be successful or long-lived without recourse to another meta-foundation, whether Christianity, liberalism, or something else. Still, from the moment it reaches to something beyond itself, populism has already started to comprise the characteristics that make it so powerfully enthralling in the first place. So much so that, while charismatic legitimacy can be infused into an institutionalized structure and meaning, it has at that point begun its inevitable dilution. (As seen recently with Italy’s conservative prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, whose last name was turned into a byword for political moderation forced on populists by institutional necessity: “Melonization.”)

As has been recently noted, much of Weber’s intellectual work was driven by his personal fixation on warding off the nihilism which he saw as inherent to modernity. Insofar as he associated this with a sterile rationalism, charisma can be seen as an attempt to avoid an empty appeal to tradition and instead reiterate another foundation to human life. Charisma, in effect, is an unavoidably religious concept. It intrinsically rejects the modern liberal notion that politics can ever really be separated from fundamental values and the conflicts they engender.

However, the fact is that Weber fails to resolve the fundamental tension between the way the charismatic seeks after the sacred and how, at the same time, it provides an ever-renewing source of creativity for new formulations of meaning. It is, from one perspective, an inevitably tragic view of life that places a certain vacuity at the heart of things: for its foundational drama is the search for a deeper reality that is, in the end, foundationless. Effective social organization, outside of the provision of baseline needs, can only be maintained through a gennaion pseudos that imposes only a partial, if not invented, view of reality.

Alternatively, Weber seems content to retrace Nietzsche’s steps in so far as he seems attracted to charisma as an experiential reality that has aesthetic, rather than metaphysical, value. That is to say, its power is not in the ends it can accomplish, but through the sort of ecstasy that can be felt through the promise or anticipation of the sacred. Although intrinsically nihilistic, it still presents something of an inverted Christian mysticism: for, to many accounts, the end stage of the process is not eventual, total union with God as much as it is eternal contemplation of that always near, always out of reach tantalizing possibility.

In the end, our political era of eccentrics is yet another indicator of the much broader socio-structural crisis of meaning, and its aspirations towards re-enchantment, produced by the sterility of liberal rationalism. While Weber, as the genius social scientist he was, can help to describe our predicament, his solution only seems to amount to a rearticulation of this deeper crisis of spirit.

Sam Routley, having previously worked in politics, is a PhD student in political science at the University of Western Ontario. A 2024–25 NextGen Fellow at Cardus, he regularly writes for The Conversation. More of his work can be found on his website. He invites you to follow him on X.

Featured image: Apotheosis of George Washington fresco (1865) by Constantino Brumidi via Wikimedia Commons.